Book Notes – So Good They Can’t Ignore You

Some highlights from reading So Good They Can’t Ignore You.

- Job: A way to pay the bills

- Career: A path towards increasingly better work

- Calling: Work that’s a vital part of your identity

Mastery & The Craftsman Mindset

The things that make a great job great… are rare and valuable. If you want them in your working life, you need something rare and valuable to offer in return. You need to be good at something before you can expect a good job.

10,000 Hours to Mastery

Mastery by itself is not enough to guarantee happiness:

- Autonomy: the feeling that you have control over your day, and that your actions are important

- Competence: the feeling that you are good at what you do

- Relatedness: the feeling of connection to other people

When you focus only on what your work offers you, it makes you hyperaware of what you don’t like about it.

The traits that define great work are bought with career capital.

RARE + VALUABLE SKILLS = CAREER CAPITAL

To earn career capital, abandon the passion mindset (“what can the world offer me?”) and instead adopt the craftsman mindset (“what can I offer the world?”).

- Craftsman mindset: What value you produce in your job

- Passion mindset: What value your job offers you

It’s dangerous to pursue more control in your working life before you have career capital to offer in exchange.

When she left her advertising career to start a yoga studio, not only did she discard the career capital acquired over many years in the marketing industry, but she transitioned into an unrelated field where she had almost no capital.

Instead of fleeing the constraints of his current job, he began acquiring the career capital he’d need to buy himself out of them. As his ability grew, so did his options. He invested his capital to gain more autonomy, this time by starting his own fifteen-person shop: He started his own company with enough career capital to immediately thrive, and had a waiting list of clients.

The strongest predictor of someone seeing their work as a calling is the number of years spent on the job. The more experience they have, the more likely they are to love their work.

- Dedication to output – obsessive focus on quality

- Track hours spent each month dedicated to thinking about research problems

- Constantly stretch and get instant feedback

- Serious study > tournaments

- More likely to find prolems at an appropriate level (just outside comfort zone)

- Pouring over books and using teachers to help identify and eliminate weakness

The Five Habits of a Craftsman

1: Decide what capital market you’re in

Winner-take-all or auction. (Diverse collection of skills, or one killer skill.)

- Winner takes all: get good at the skill above all else

- Auction: There are many different types of career capital, and each person might generate their own unique collection.

Mistaking a winner-take-all for an auction market is common. (Hollywood is winner-take-all. Don’t get job at National Lampoon thinking you’re building skills.)

2: Identify the specific type of capital to pursue

- Winner takes all: there’s only one type of capital

- Auction: Seek opportunities to build capital that are already open to you. Open gates get you farther faster.

Think about skill acquisition like a freight train: Getting it started requires a huge application of effort, but changing its track once it’s moving is easy. In other words, it’s hard to start from scratch in a new field.

3: Clear goals

For a script writer, the definition of “good” was clear: his scripts being taken seriously.

4: Deliberate practice

Consistently push slightly beyond comfort zone and get feedback regularly

- Use a time structure (1 hour, or pomodoro)

- Use an information structure (capture results)

- Proof map → quiz → proof summaries

5: Look years into the future for the payoff.

Ignore other pursuits that pop up along the way to distract you.

Three Disqualifiers for Applying the Craftsman Mindset:

- The job presents few opportunities to distinguish yourself by developing relevant skills that are rare and valuable.

- The job focuses on something you think is useless or perhaps even actively bad for the world.

- The job forces you to work with people you really dislike.

Cal’s Workflow

Shutdown Ritual Daily

- Via website, not in book.

- Summarise the day

- Review calendar, tasks, emails

- Add any thoughts or actions to your plan for the week

- Spend 20-30 minutes immediately after focused on a non-work thought (or task – mowing the lawn etc), or focus on a single thing like book or podcast. The focus on a single thing helps the other parts of your brain shutdown and cool off

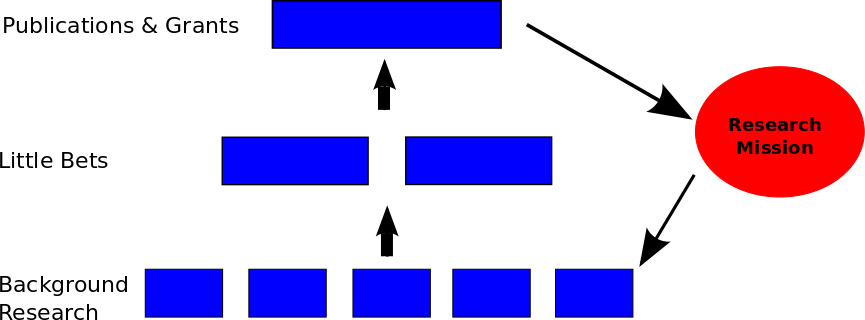

Background Research Weekly

- Expose yourself to something new in your field every week

- Summarise it in your “Research Bible”

- A description of the result

- How it compares to previous work

- The main strategies used to obtain the result

- 1 walk every day to think about it

Little Bets Monthly

- Turn a vague mission in to specific projects

- Explore most promising ideas from background research

- Small enough project to be completed in less than a month

- Forces you to create new value (master a new skill, produce new results, etc)

- Provides a concrete result that you can use to gather concrete feedback

- Use deadlines to help keep urgency of completion high

- Only 2 or 3 active at one time

- Record results, by hand, on a dated page

Mission Yearly

- Rough guideline of the type of work or outcome you’re aiming at

- Can only find missions when you can see the adjacent possible

- Can only see the adjacent possible from the cutting edge

- Can only get to the cutting edge with career capital

Accountability

- Track number of hours in a state of deliberate practice

Great missions are transformed into great successes as the result of using small and achievable projects—little bets—to explore the concrete possibilities surrounding a compelling idea.

Once a week I require myself to summarize in my “bible” a paper I think might be relevant to my research. This summary must include a description of the result, how it compares to previous work, and the main strategies used to obtain it.

…sheet has a row for each month on which I keep a tally of the total number of hours I’ve spent that month in a state of deliberate practice.

At the end of each of these brainstorming sessions I require myself to formally record the results, by hand, on a dated page.

“When deciding whether to follow an appealing pursuit that will introduce more control into your work life, ask yourself whether people are willing to pay you for it. If so, continue. If not, move on.”

…just how tricky it is to make this trait a reality in your working life. The more you try to force it, I learned, the less likely you are to succeed.

First you need career capital, which requires patience. Second, you need to be ceaselessly scanning your always-changing view of the adjacent possible in your field, looking for the next big idea. This requires a dedication to brainstorming and exposure to new ideas. Combined, these two commitments describe a lifestyle, not a series of steps that automatically spit out a mission when completed.

My system is guided, at the top level of the pyramid, by a tentative research mission—a sort of rough guideline for the type of work I’m interested in doing.

…bottom level, where we find my dedication to background research.

Every week, I expose myself to something new about my field.

To ensure that I really understand the new idea, I require myself to add a summary, in my own words, to my growing “research bible”

I use little bets to explore the most promising ideas turned up by the processes described by the bottom level of my pyramid. I try to keep only two or three bets active at a time so that they can receive intense attention. I also use deadlines, which I highlight in yellow in my planning documents, to help keep the urgency of their completion high. Finally, I also track my hours spent on these bets in the hour tally I described back in the section of this conclusion dedicated to my application of Rule #2. I found that without these accountability tools, I tended to procrastinate on this work, turning my attention to more urgent but less important matters.

Working right trumps finding the right work—it’s a simple idea, but it’s also incredibly subversive, as it overturns decades of folk career advice all focused on the mystical value of passion. It wrenches us away from our daydreams of an overnight transformation into instant job bliss and provides instead a more sober way toward fulfilment.

Most individuals who start as active professionals change their behaviour and increase their performance for a limited time until they reach an acceptable level. Beyond this point, however, further improvements appear to be unpredictable.

The traits that Anders Ericsson defined as crucial for deliberate practice.:

- He stretched his abilities by taking on projects that were beyond his current comfort zone…

- He then obsessively sought feedback

When running his start-up, this feedback took the form of how much money came through the door. If he ran the company poorly, there would be no escaping this fact: His critique would arrive in the form of bankruptcy.

A spreadsheet, which he uses to track how he spends every hour of every day. “At the beginning of each week I figure out how much time I want to spend on different activities. I then track it so I can see how close I came to my targets.”