Book Notes – The Oregon Experiment

Organic Order

A process that allows the whole to emerge gradually from local acts.

In a complex system you can’t possibly envision every single detail, interaction and change in the context, so trying to plan it all up front is futile. You end up with a collection of parts dumped together that don’t interact well.

Compare a DJ set against a playlist created at the start of the year. The DJ will feel the mood of the room. They’ll up the tempo to get people to dance. They’ll slow it down to encourage visits to the bar. A playlist just continues on no matter what. It can’t add new hits. It can’t remove songs that were good in theory but the crowd can’t get into.

Organic order is achieved by following a process instead of sticking to a plan.

Participation

Decisions about what to build will be in the hands of the users.

Participation in the development process strengthens the community of users of the system. It gives them skin in the game. Daily users of the system are better informed about their needs than anyone else, so their input tends to create forms that are better adapted to those needs.

The group setup is important. A core, representative group of up to 7 users leads the project, calling in specialist advisors as required. Only projects initiated by user groups should be considered for funding. User groups should be allocated adequate time to be involved in the development of the system with equal priority to their regular activities.

Shared principles – patterns – are needed to ensure that order is not replaced by chaos. Projects must not be sized so large that a small group cannot be responsible for the whole design. Large projects are so complex that it’s hard not to discuss them in abstract terms and focus on less ambiguous minutiae. Correctly sizing projects allows conversations and design to happen with enough clarity at the right level of abstraction. Minutiae is left until later, but the bones of the design are based on concrete understanding of the context.

Piecemeal Growth

Budgets should be weighted in favour of small projects.

Growth and repair is an expected part of any living system, as is adaptation to changing contexts. Changes are expected; they should happen gradually, and be distributed evenly across every level of scale. Piecemeal growth assumes mistakes are inevitable. As much attention should be given to repair and repurposing as it is to new creations.

The opposite of piecemeal growth is “large-lump development”. Growth happens in large chunks and pieces are often assumed to have a finite lifetime until they are discarded. Large-lump development is based on the assumption that you can make a perfect form first time. Repair is minimised and they are rarely adapted to changing contexts. This leads to an extremely short useful lifespan.

Centralised budgeting encourages large-lump development. Competition for the limited number of grants is high so each project’s needs are exaggerated to hedge against failure to acquire follow-on funding. Since maintenance and repair are bottom of the list, there are always large parts of the environment that end up chronically under-maintained to the detriment of the whole.

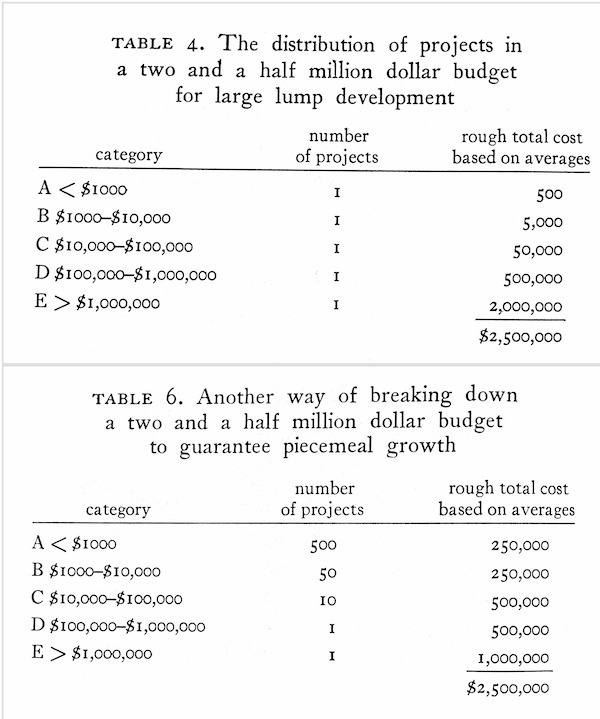

Don’t specify a budget ceiling; specify a budget distribution. Ensure the same total amount of money is spent on smaller projects than it is on larger projects. Accept that it is not possible to examine every small project in detail before it receives funds – trust that the users have made good decisions.

Examples of piecemeal growth vs large-lump development budget distributions.

Patterns

Development should be guided by a communally adopted pattern language.

A pattern is a generalised solution to a clear problem that may occur repeatedly in a particular context. For example, a home will generally require a kitchen, some bedrooms and a bathroom. A kitchen will require a heat source, a sink, some storage and possibly a refrigerator. The implementation details – size, materials, layout, etc – will be guided by the local context, but the bones of the solution are generally similar where the pattern is applied.

Patterns are independent – they make sense one at a time – and can be formed in to a collection that makes sense as a whole. A pattern language is the agreed set of patterns for a system or community. A pattern language will likely contain some very general patterns and some very specific to the specific environment. The pattern language should be reviewed on an appropriate recurring interval and, driven by empirical evidence, tweaked, added to and replaced over time.

Diagnosis

Regular diagnosis protects the wellbeing of the whole.

Where does global order come from without a master plan? How can we be sure that thousands of piecemeal developments won’t result in chaos? It is easily possible that users with less experience of implementing the patterns will fail to infer direction from them or lack understanding of how to integrate them.

The problem is solved by a process of diagnosis and local repair. Diagnosis helps define a bounded context and within it identify places where the patterns have broken down. The pattern language helps offer a controlled set of options for remedying the area. Our feelings will always outstrip the available set of patterns, so we must be free to include these in any diagnostic process as well as noting the lack of conformity to the pattern language.

This is the opposite of a master plan approach. A master plan tells us what is right for the future. Diagnosis tells us what is wrong in the present. This has the effect that any project is driven by a demonstrated, concrete need and has a constrained set of solutions in the form of the pattern language. This is entirely different than attempting to predict future needs with no constraints on what can be built. Even experienced developers will fail at the latter.

Coordination

The funding process should regulate the stream of projects.

A centralised budget is never ideal, as there’ll always be a group that holds more power over how it gets used. Organic order will only grow under conditions where individual acts are free and coordinated by mutual responsibility, not by constraint or control. The examples here are an attempt to simulate organic order within the context of a centralised budget and planning committee.

Budgets will be evenly distributed across project sizes so that projects of different sizes will not compete for funds. There should be allotted periods where projects are assessed against each other in their size range and prioritised. The process of project selection and the ensuing debates around them should be clear and public. The smaller the project, the quicker the approval process should be to ensure enthusiasm is maintained.

Projects submitted for approval must explain their relation to the pattern language and diagnosis. A standard form should be used for project proposals so that they can be compared equally. It must state the design of the solution, cost, source of funds, and illustrate the conformity or non-conformity to all patterns in the pattern language and diagnosis. All kinds of projects must go through this process – repair, maintenance, new growth – so that the whole is always considered at every level.