Book Notes – Competing Against Luck

Introduction

Customers don’t have “problems”. They struggle to make progress.

Quantitative data doesn’t tell you about the situation customers are in, or why they choose one product over another to help them.

A good theory helps understand the “how” and “why” instead of relying on trial and error for innovation.

Jobs Theory (AKA Jobs To Be Done) helps you understand the cause and effect of the choices they make during their struggle.

Chapter 1: The Milkshake Dilemma

Situation and circumstance have more of an effect on whether your product or service can help a customer make progress.

Different circumstances have different evaluation criteria that you may not be expecting. You must evaluate whether your solution is good enough in the context of the situation.

You don’t use a bicycle in a motor race, and you drive a sports car cross country. Something that’s well designed for one situation can be a total failure in others.

It’s difficult for competitors to copy well-integrated experiences. If you understand the underlying causal mechanism of the progress a customer is trying to make, you can fully support them in that situation – not just in the use of the product but in all the context around the purchase too.

Chapter 2: Progress, Not Products

JTBD is a theory for how to think rather than a concrete process to follow.

A Job is defined by the progress people are trying to make in particular circumstances. Jobs have inherent complexity. They include the functional, social and emotional forces that cause people to make tradeoffs when making choices.

Correlation through attribute-based research helps narrow the possibilities of why someone may choose A or B, but doesn’t get at the root cause which explains how the choices were made and how to get repeatable results. Deconstructing complex experiences into binary data destroys meaning that allows us to understand the causal mechanism. Great innovation insights come through depth, not breadth.

“Needs” are too abstract and have no situation attached to be able to define causality. Jobs is about clustering similar stories instead of segmenting details.

Jobs only applies where there’s a struggle for progress. There’s always more than one solution to a Job, including taking no action. Circumstance actually changes the competitive field.

Chapter 3: Jobs in the Wild

It’s easy to get sucked in to competing on features with existing players in the same industry. Jobs helps you compete for different situations. (See Blue Ocean Strategy for more on this).

Fully integrating around a Job means building the right set of experiences in how customers find, purchase and use your product.

Negative Jobs – where someone wants to make progress by not doing something are often fruitful situations to explore.

Non-consumption is often the biggest competitor.

Chapter 4: Job Hunting

Enabling something new can often be more valuable than producing something new.

You can find Jobs where you see barriers to progress; Jobs in your own life; non-consumption; workarounds; unusual uses; things people don’t want to do. You often won’t see these anomalies unless you’re fully immersed in the context of their struggle.

Uncovering Jobs adds narrative – language and causality – to complex processes instead of a few scattered frames, telling you which pieces of information are needed, how they relate, and how they can be used create value.

Chapter 5: How to Hear What Your Customers Don’t Say

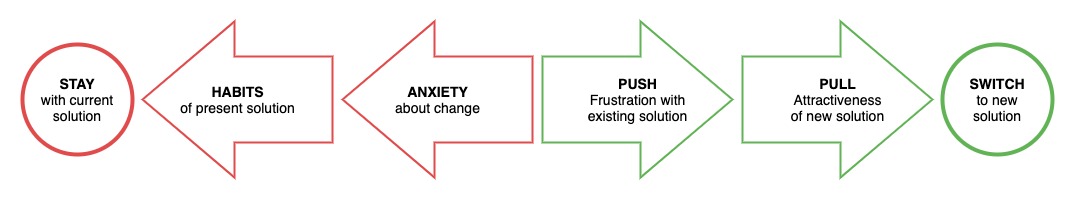

In order to hire a new solution, by definition customers must fire the suboptimal solution or compensating behaviour (including doing nothing).

The forces compelling change must outweigh the forces opposing change for a customer to switch. People’s tendency to want to avoid loss is twice as powerful as the allure of gains.

- Big Hire: The moment you buy a product.

- Little Hire: The moments you actually use the product.

Tracking Big Hire moments doesn’t reveal whether your product helps the customer make progress through repeated Little Hires. Failing in Little Hire moments pushes people towards a new solution.

It’s rare for people to be able to articulate what they want, but they can tell you about their struggles. Observing what they actually do tells a story that preference-based data can’t. Look for recurring moments of struggle and identify when the forces impact decision-making. Understand the narrative in such detail that you can design a solution that far exceeds anything they could come up with themselves.

Chapter 6: Building Your Résumé

Focusing on making the product better often misses the most powerful causal mechanism of making the experience better.

Businesses succeed because of the experiences they enable, not the features and functionality they offer. It’s rare that the product itself is the source of long-term competitive advantage. Everything about the experience must integrate around the Job.

- Uncover the Job – progress + situation; functional, emotional and social dimensions.

- Create the Desired Experiences that existing solutions fail to provide in the circumstances of the Job.

- Integrate internal processes around the Job to deliver the Desired Experiences at every touchpoint.

People will always factor in cost and quality when making a decision, but also priorities and tradeoffs. People will make the tradeoff of paying premium prices when the full cost of alternatives is too high. Poor solutions focused on low cost can cause anxiety – a push to alternative solutions.

You should consider who shouldn’t use your product to avoid a mismatch in expectations.

Organisations can lose their understanding of the Job that made them so successful when they continuously try to add new benefits and features to expand horizontally across the market.

Chapter 7: Integrating Around a Job

If you can’t describe what you are doing as a process, then you don’t know what you are doing.

– W. Edwards Deming

Processes touch everything about the way an organisation transforms its resources into value, and profoundly affect long-term success. Unlike resources, processes can’t be seen on a balance sheet.

Ensure that the Job, not efficiency, productivity or hierarchy, remains the focal point for innovation. Processes should optimise around how different parts of the organisation interact to systematically deliver the experiences necessary to satisfy the Job. Processes are much harder for competitors to reverse-engineer.

Processes aligned with Jobs shift complexity and nuisance from the customer to the vendor. Measure success based on externally relevant customer benefit metrics, not internal performance criteria. This is difficult.

The world will change around you, so how you solve the Job over time will change but the Job itself will not. Changing solutions may seem impractical culturally or financially, but these can be optimised later. Make it work; make it good; make it cheap; make it good and cheap.

Chapter 8: Keeping Your Eye on the Job

The Fallacy of Active vs Passive Data: Passive data found in the context of the struggle has limited structure that requires uncovering narrative to innovate on. Active data from operations is structured and easy to track and measure and creates a model of reality. Mistaking the model created by active data for the real world of passive data is poison for innovation.

The Fallacy of Surface Growth: Companies are naturally inclined to sell more products to existing customers, leading them to lose focus on the Job that brought them success in the first place. Each new Job that you try to solve brings several competitors who focus only on that Job. Now you’re not the best at solving any Job.

The Fallacy of Conforming Data: We focus on signals that tell a story of the world as we would like it to be, rather than how it really is. The healthiest mindset for innovation is that nearly all data is built upon human bias and judgement. You must be constantly vigilant against perceiving models of the world as reality.

Chapter 9: The Jobs-Focused Organisation

Many companies struggle to translate mission statements into everyday behaviours. A well-articulated Job provides a “commander’s intent” – a focal point for employees to make the right decisions without being told specifically what to do each time.

“What get measured, gets done” is only useful if what’s being measured is helping the customer make progress. Managers must frame work as effectively resolving customers’ Jobs, not as efficiently executing internal processes.

Jobs provides a compass for how to shape solutions but is also a filter for what not to do.

Chapter 10: Final Observations About the Theory of Jobs

A Job is a construct – an abstraction that’s rarely directly observable. Jobs is a stepping stone that helps us see the dynamics of causality.

A Job is intentionally precise and there are boundaries of the theory.

Not everything that motivates us is a Job to Be Done. A well-defined Job is expressed in verbs and nouns, not adjectives and adverbs.

You’re not at the right level of abstraction and you’re not uncovering a Job if only products in the same class can solve the problem.