Programming for Humans

Programming for Humans is a talk I gave last year to a tutorial session for students of a foundation course for Computer Science at Royal Holloway University of London, organised by an ex-mySociety colleague.

I’m going to talk to you about programming for humans.

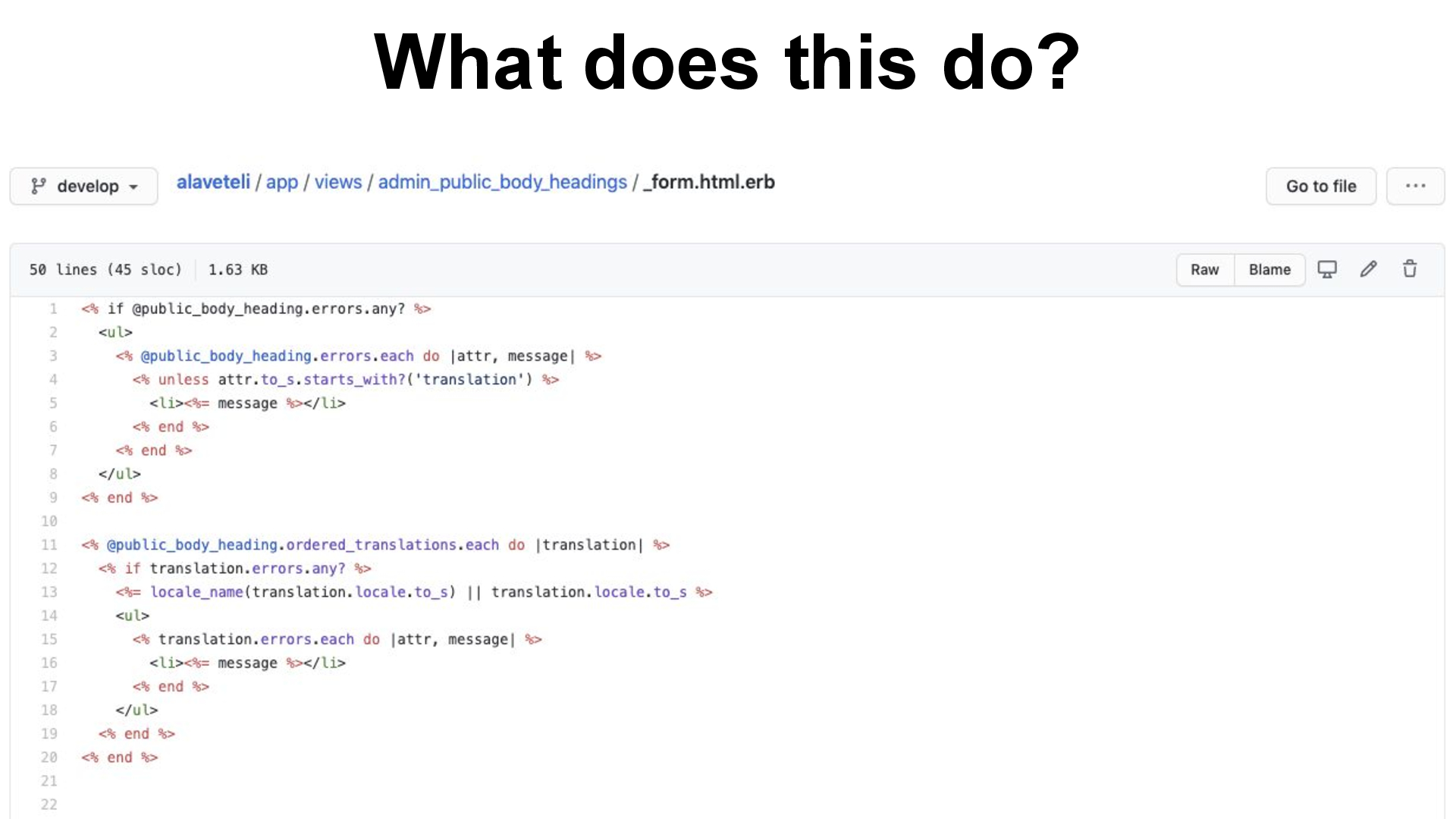

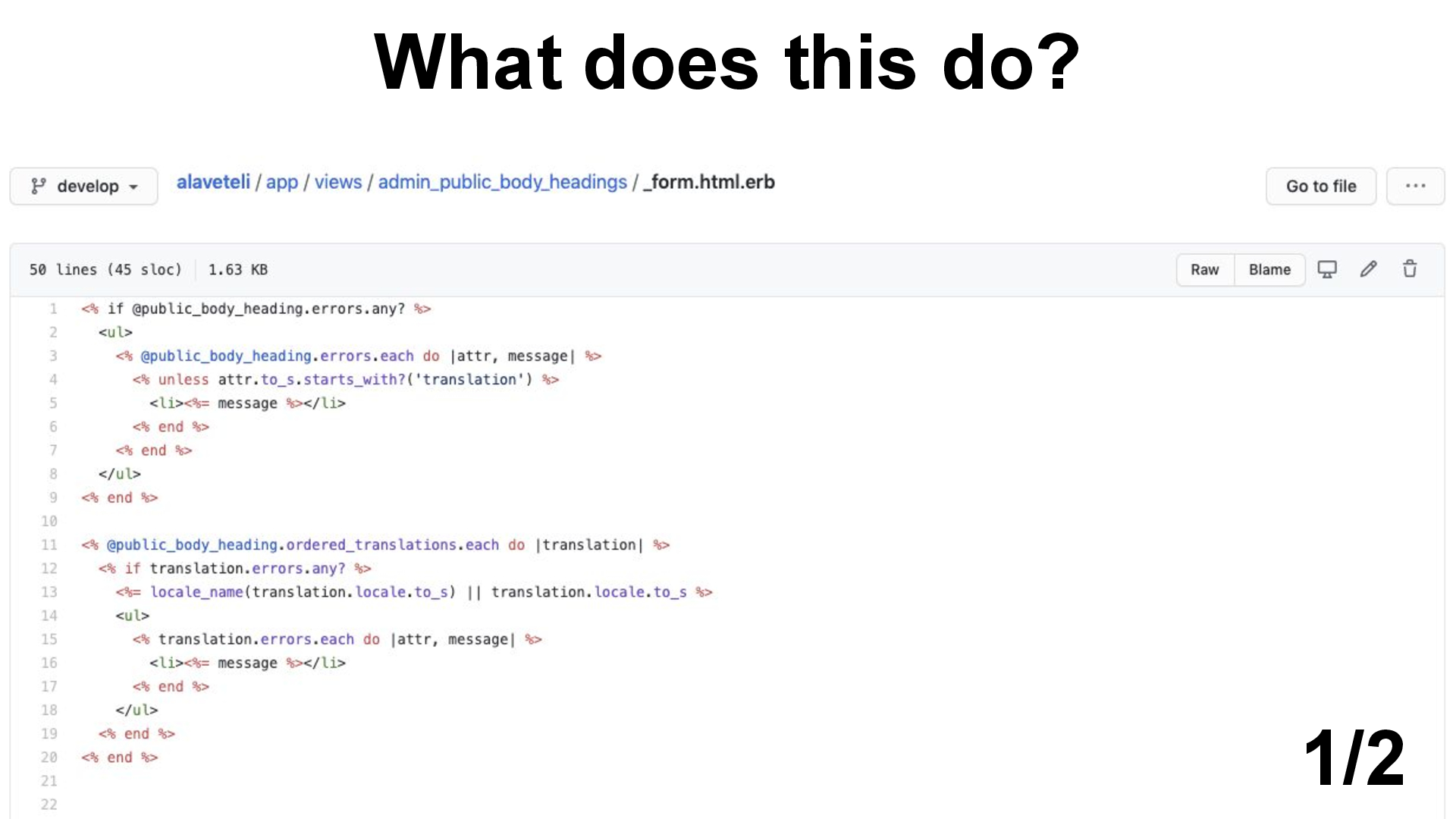

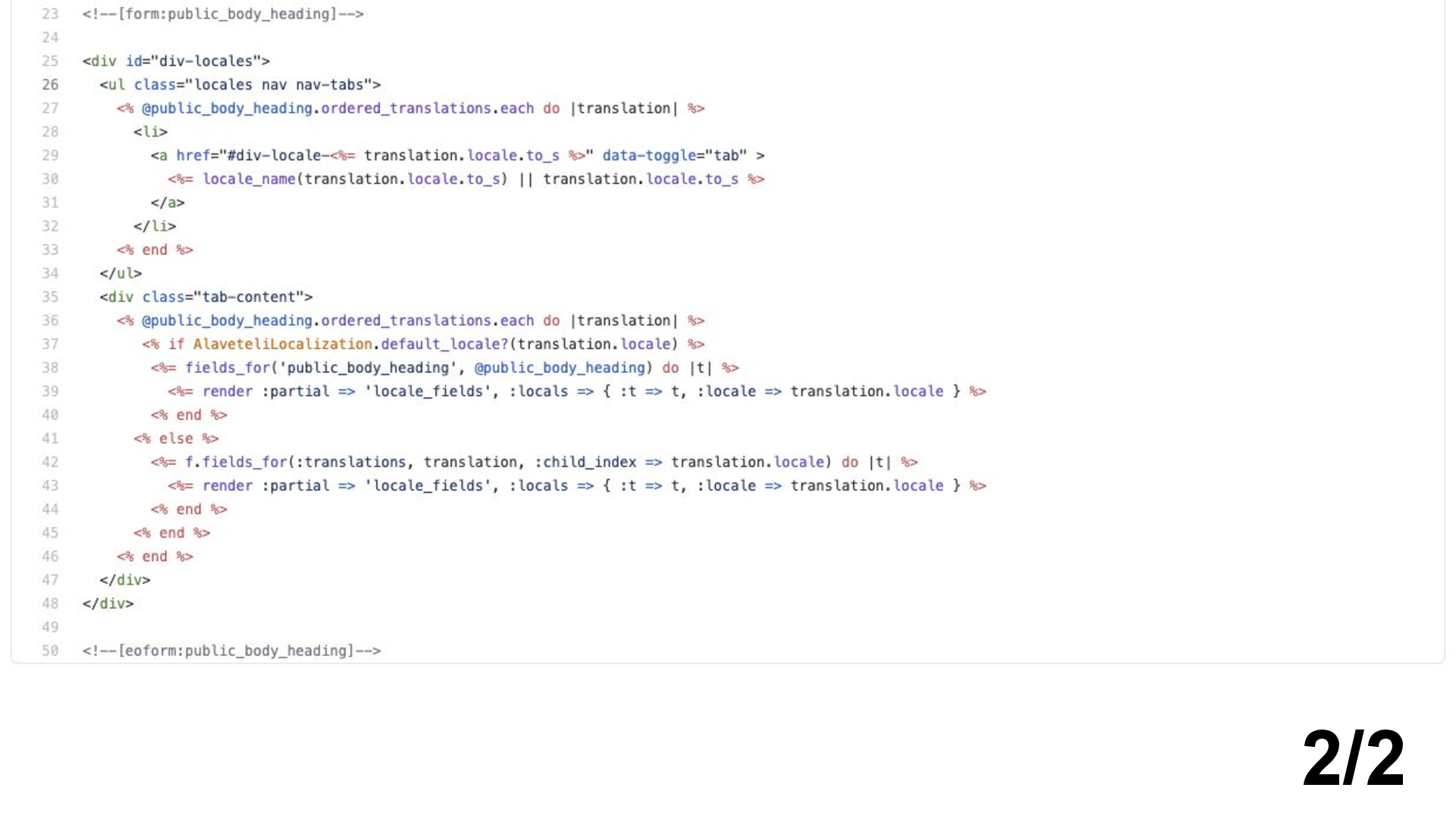

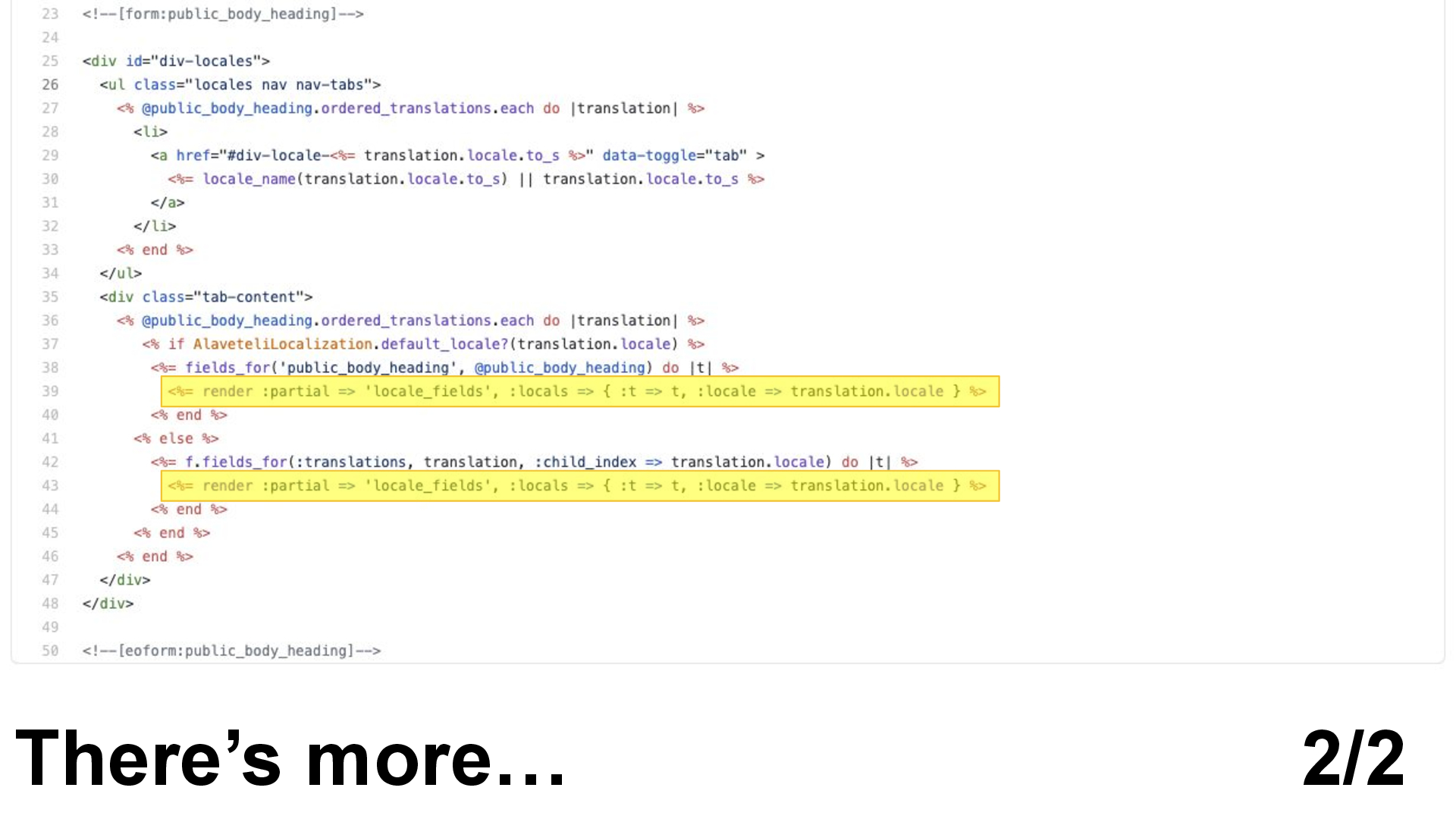

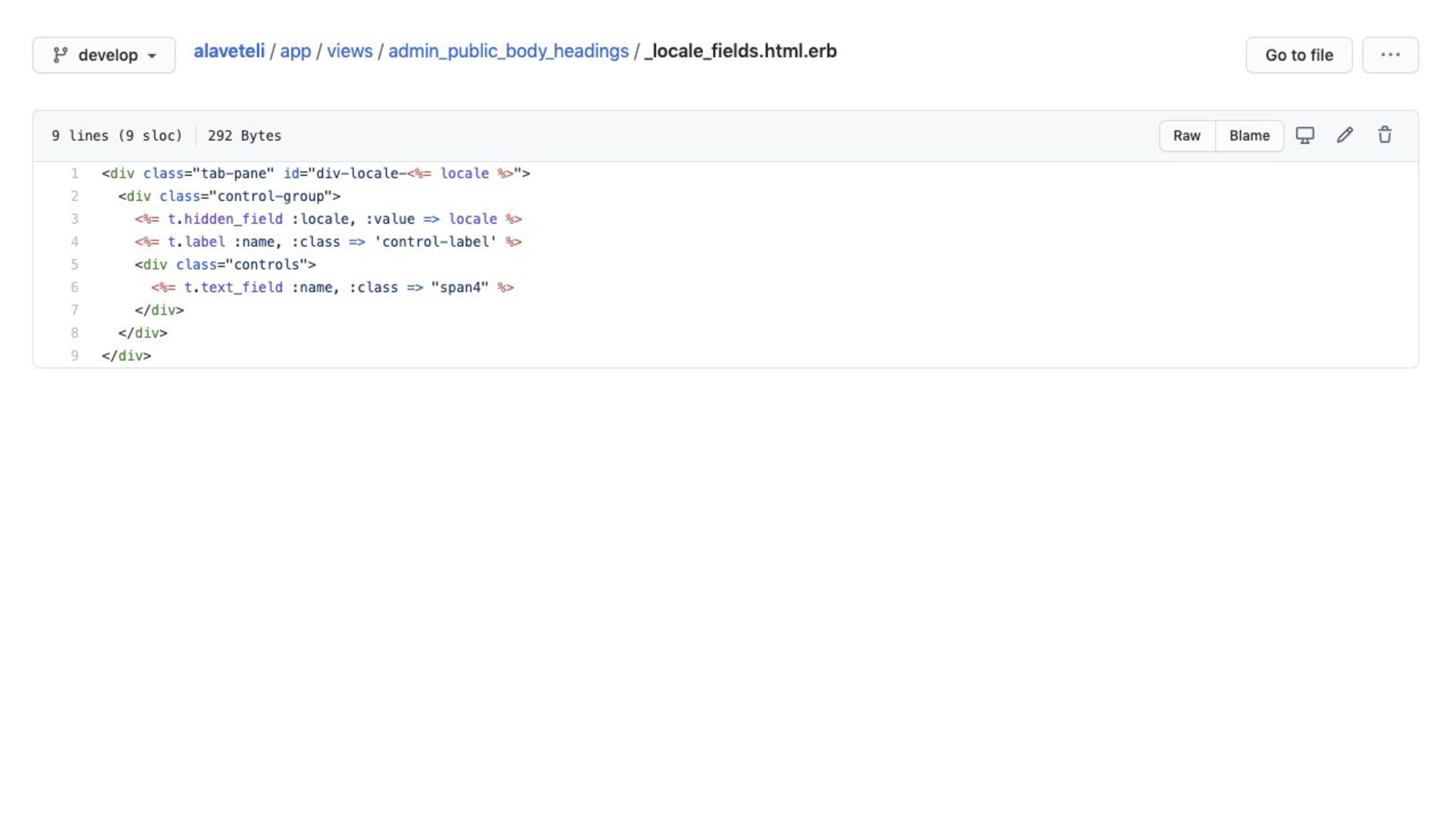

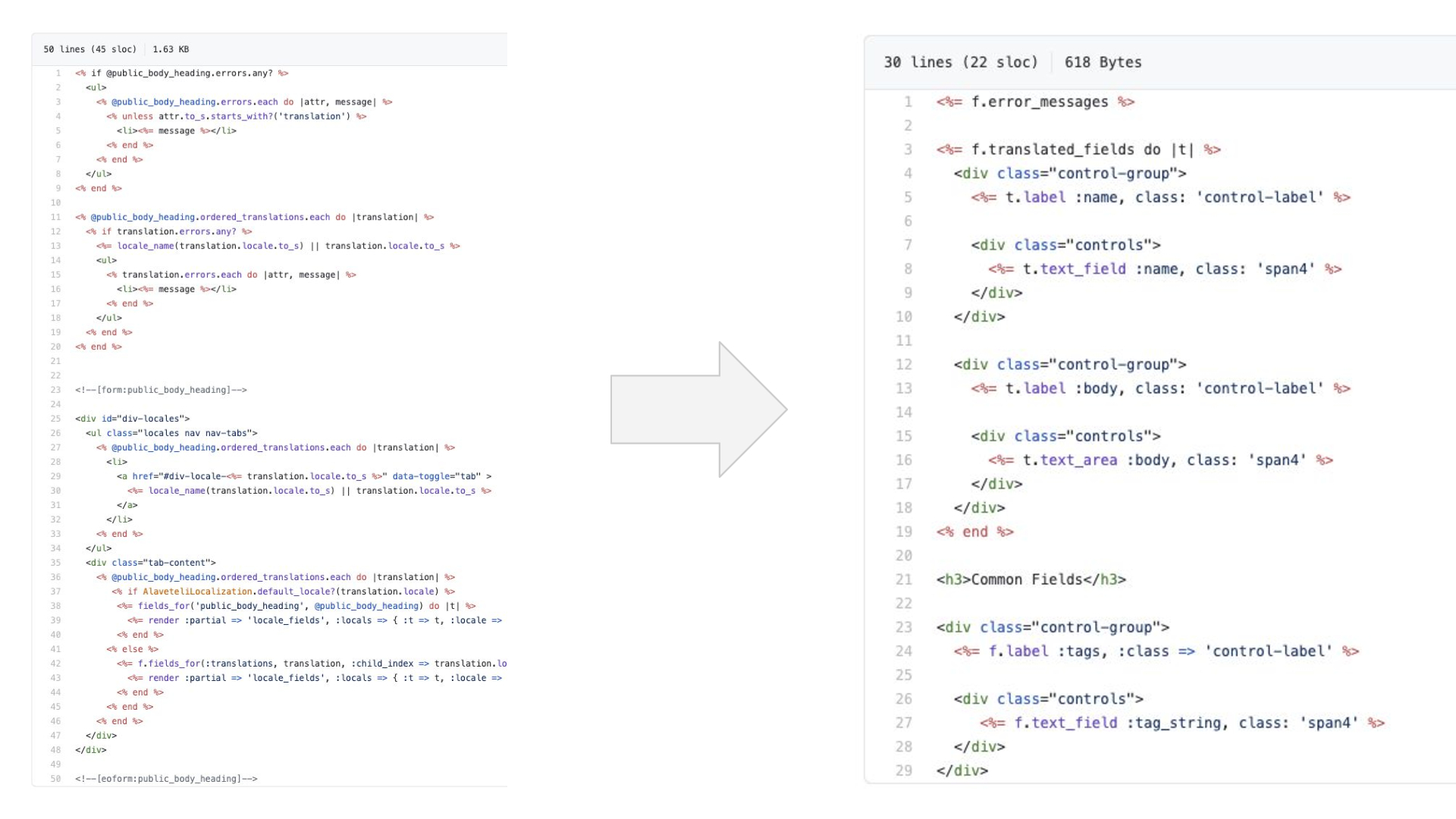

What does this do?

But not just this…

Here’s the other half of the file.

But there’s more. These lines include some more code…

…which renders some more stuff…

All that code is for rendering this!

But I don’t mean the whole page…

…just this section of a form with one field and some tabs for each translation of the value.

This was a question I was asking myself at the start of last week.

We’ll get back to this later.

Hey!

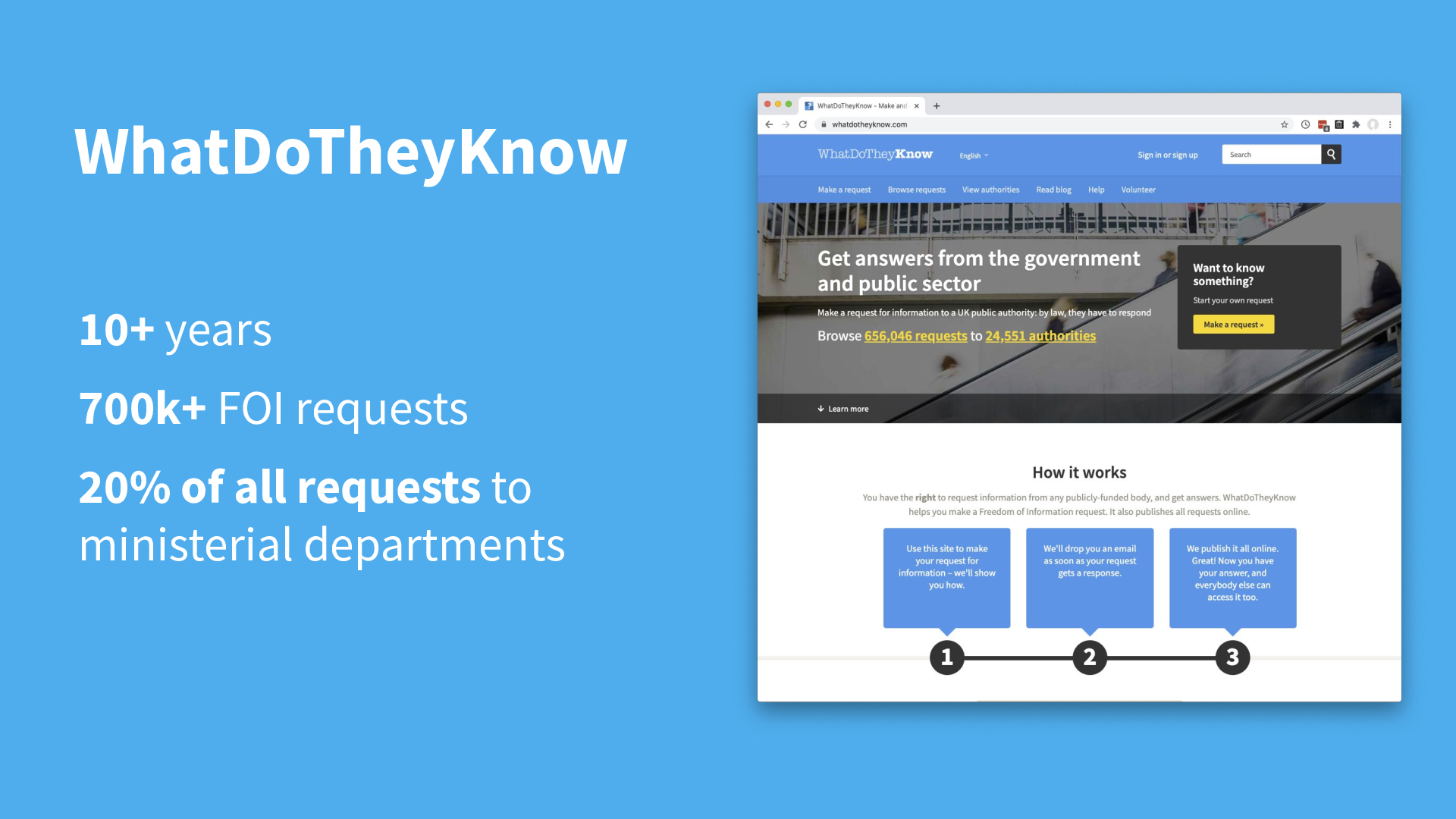

I’m Gareth and for the last 7 years I’ve been a programmer at mySociety…

We’re a civic tech charity and we make web services that help citizens hold power to account, engage in democracy and improve their local communities.

Most of my work is around WhatDoTheyKnow.com, a service that makes it easy to ask for information from public bodies.

It’s been running for over 10 years and accounts for around 20% of Freedom of Information requests in the UK.

It uses an open source Ruby on Rails platform that we built called Alaveteli, which is installed in about 25 jurisdictions around the world.

When I started university this was the state of mobile phones…

We’ve moved on a bit!

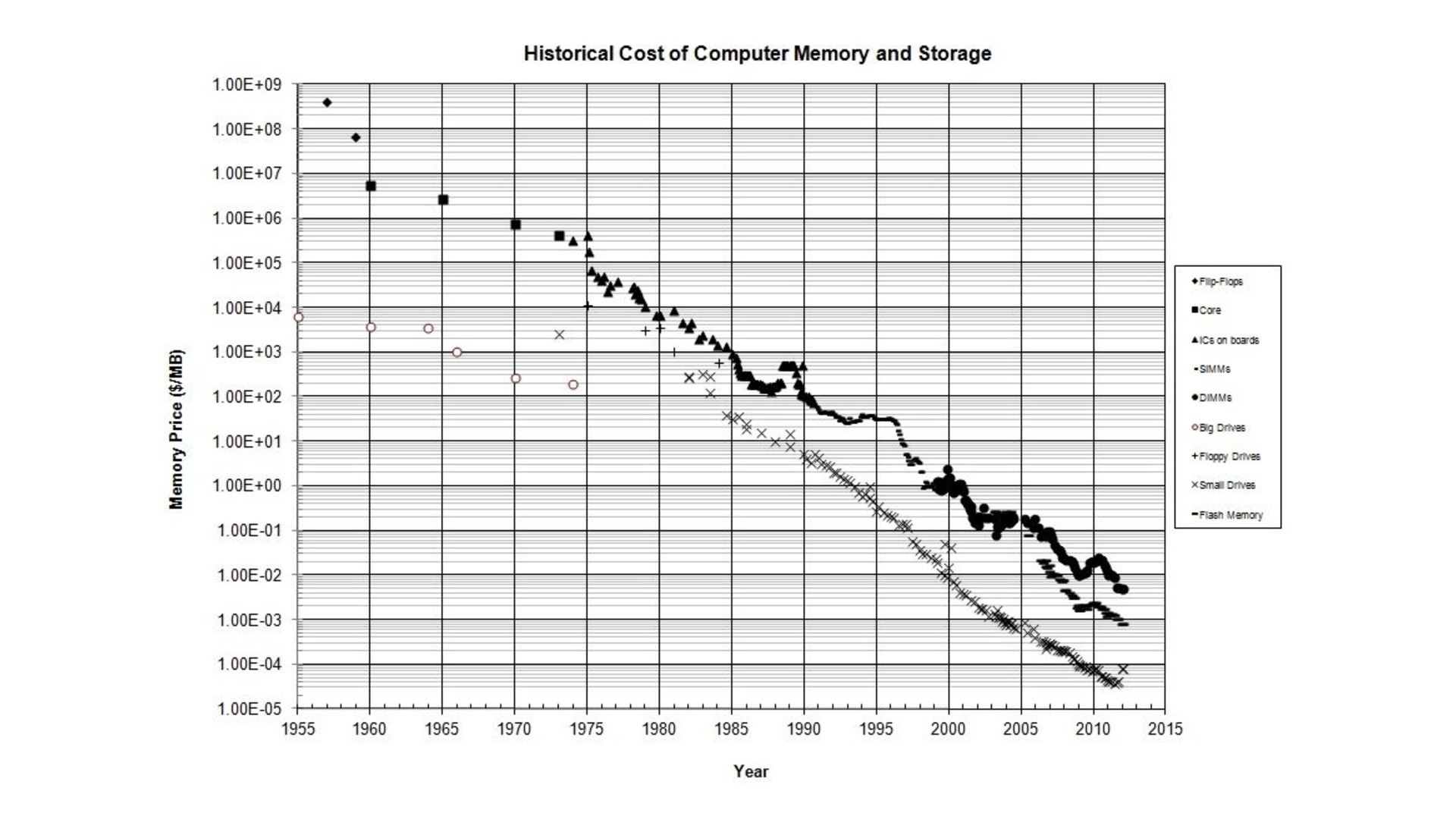

It’s probably obvious to most people that over time computer performance goes up while cost comes down.

But what hasn’t changed so much in all that time is the performance of the human brain.

Why does this matter?

We actually spend most of our time reading code rather than writing it.

In pretty much any software that’s not a hobby project, you’ll have more than one person working on it, so you’re often reading someone else’s code before you start writing your own.

Or you’re trying to remember what you yourself wrote 6 months ago!

It can feel like this a lot of the time.

This is exactly how I felt while I was trying to understand the code I showed you earlier.

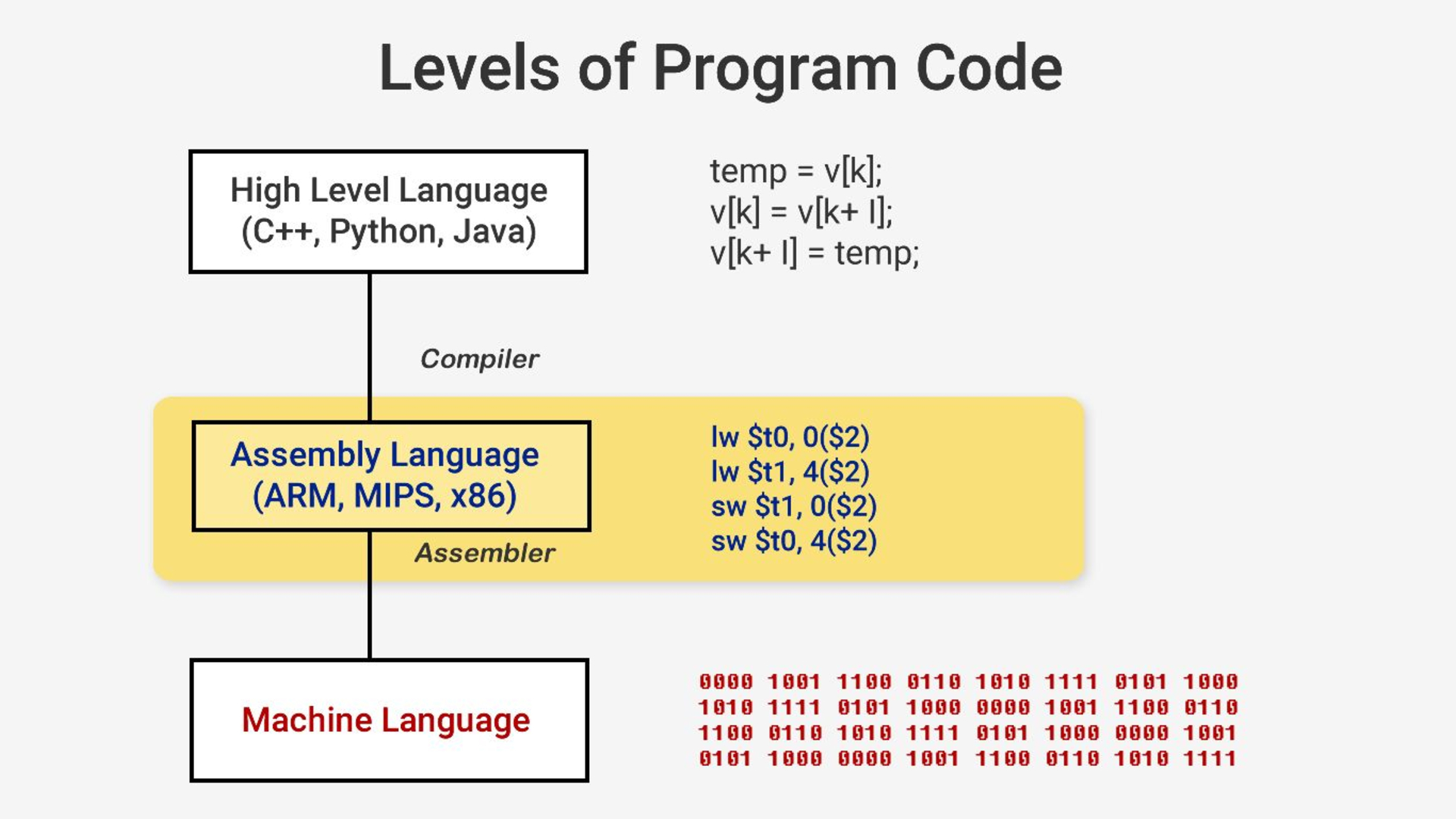

Sometimes, you are actually trying to understand some really difficult concepts…

But more often than not it’s because what a machine understands is very different to what a human understands.

Fortunately, we’ve used the performance improvements in computer hardware to create languages that are easier for humans. We’re not writing machine code or assembly language day to day any more.

But even with these better languages, it’s still up to programmers to use them in a way that other programmers can understand.

We’ve all written essays and had them handed back like this.

Writing is hard.

It takes a lot of work to explain things coherently, and it’s no different with programming.

Finding the right words and concepts is one of the most difficult but important things you can do as a programmer.

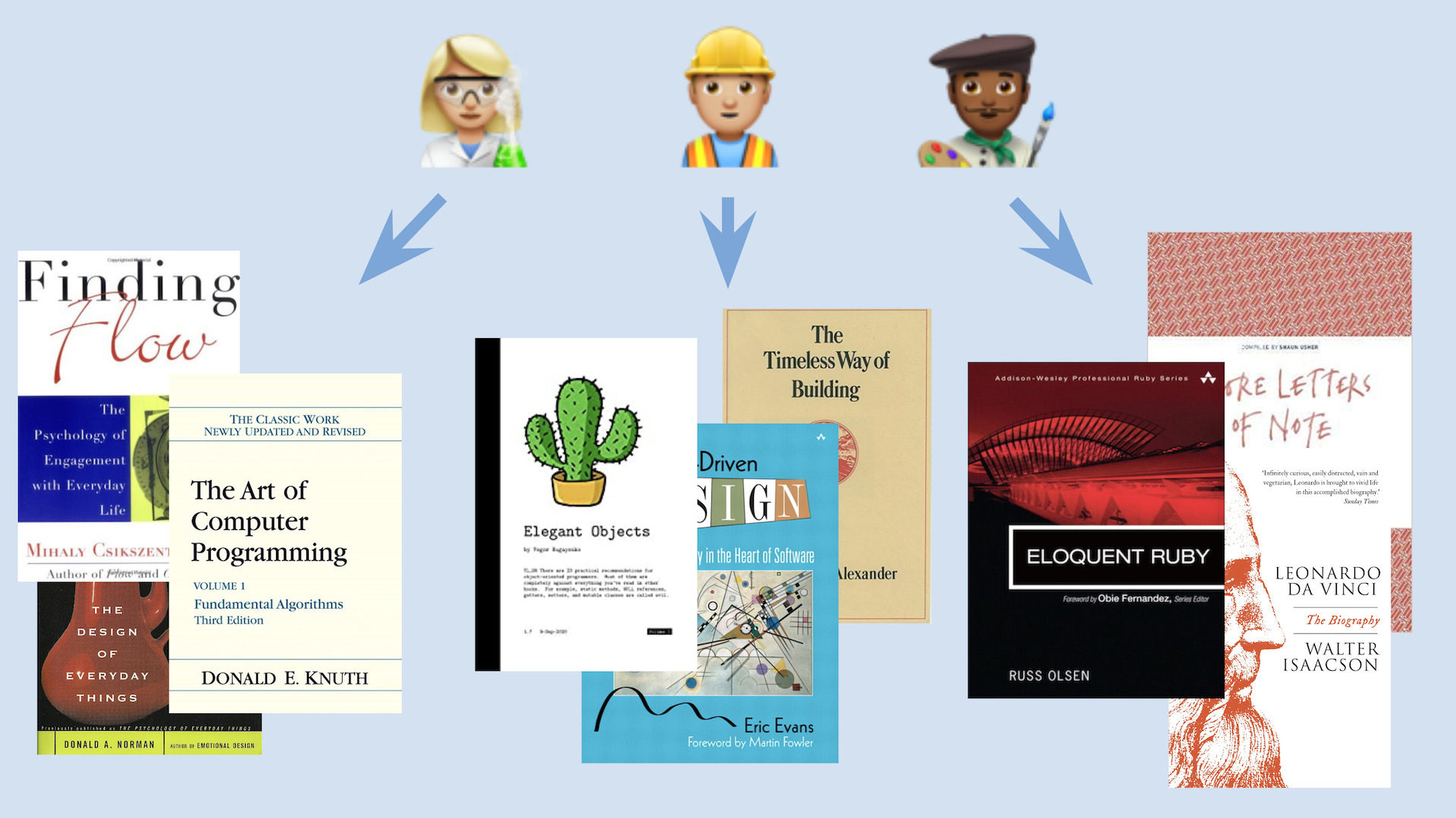

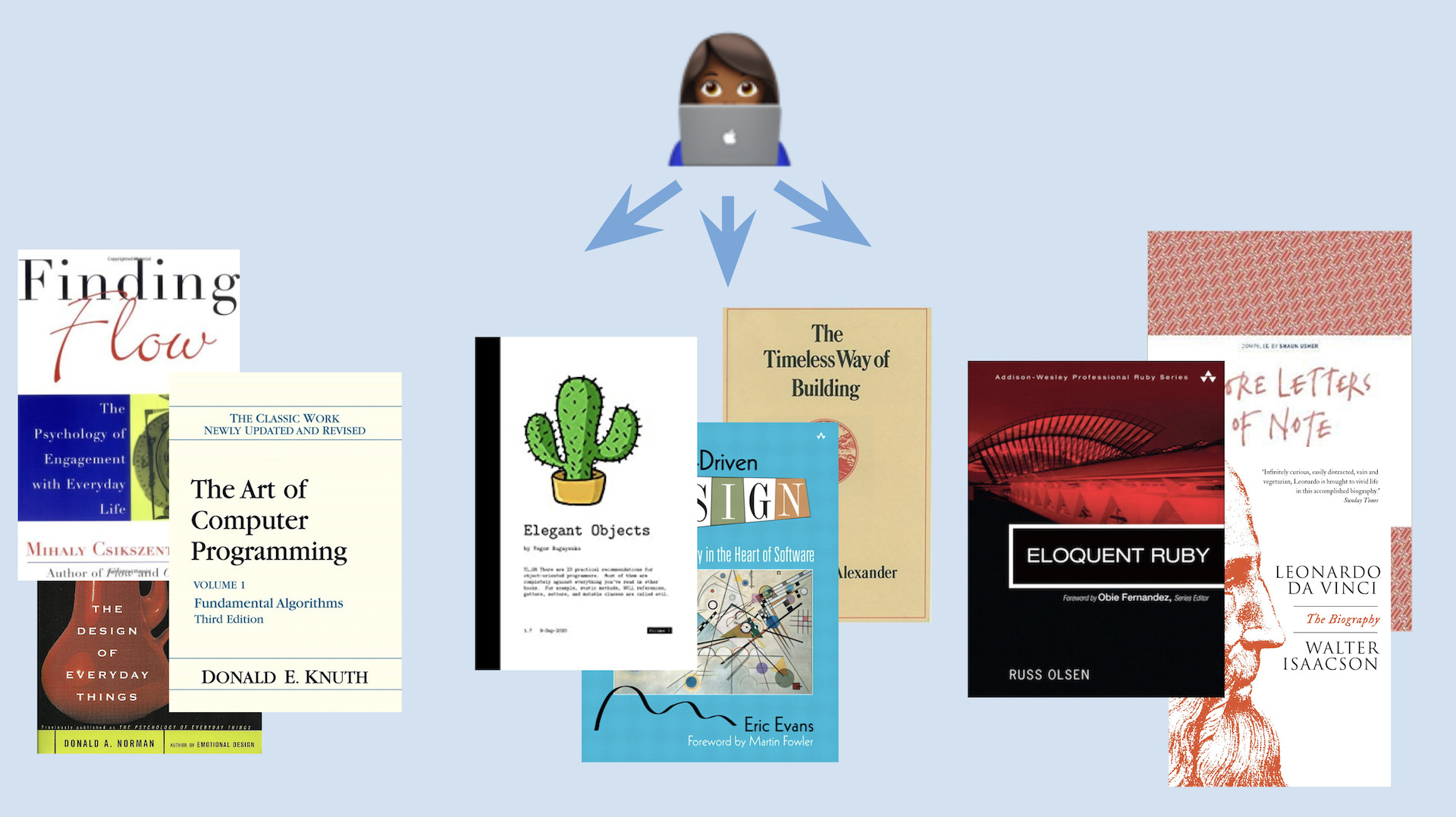

Programming is a science, but it’s also engineering, and it’s also an art.

This often gets forgotten because we spend so much of our time looking at code and dealing with machines.

What makes life difficult for programmers is that we’re trying to communicate with both machines and humans at the same time.

Believe it or not, this is JavaScript, a fairly readable language.

It’s been compressed so that it’s quicker to send to a browser. Quicker for machines.

Machines can interpret this, but I sure as hell can’t.

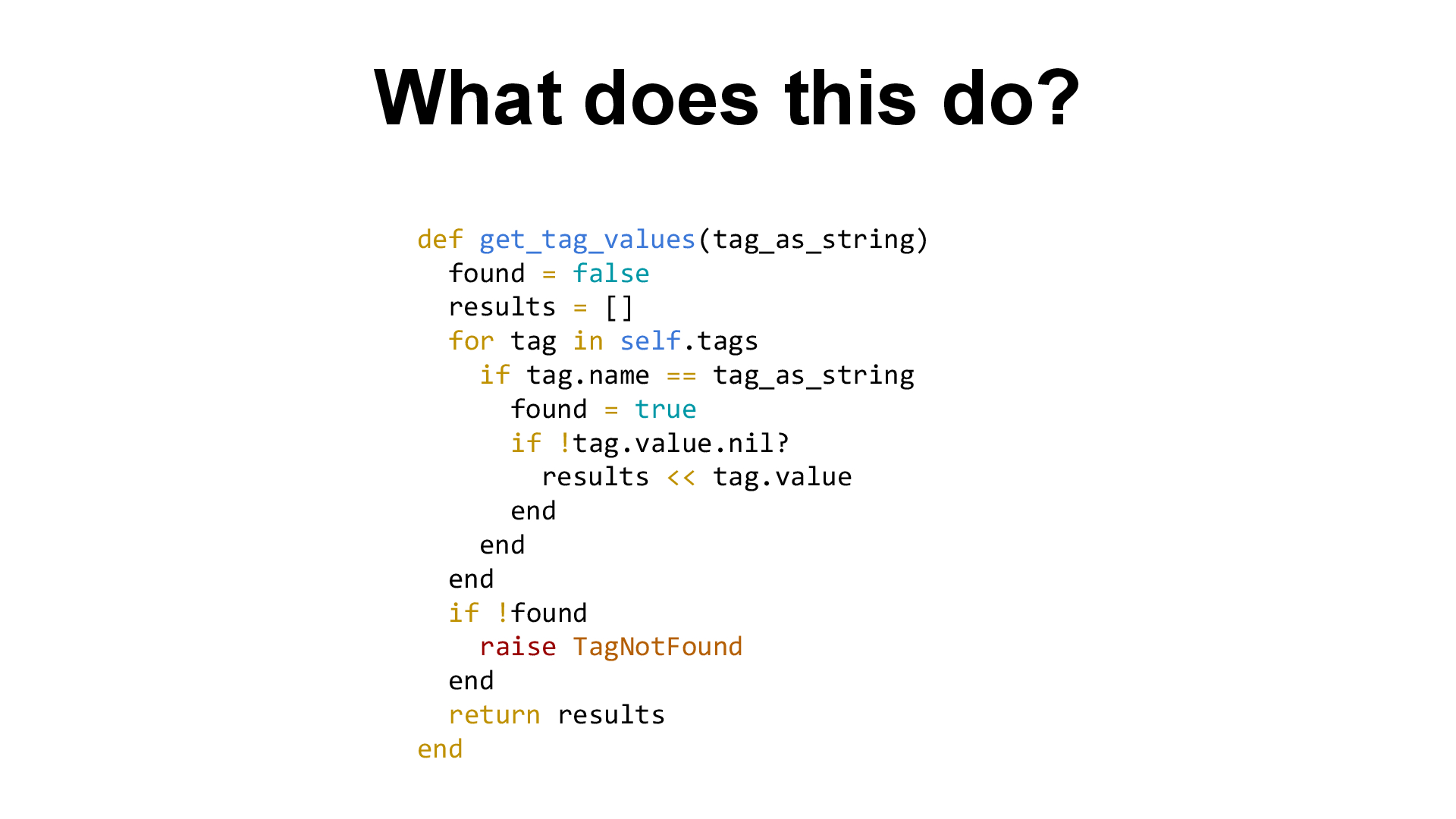

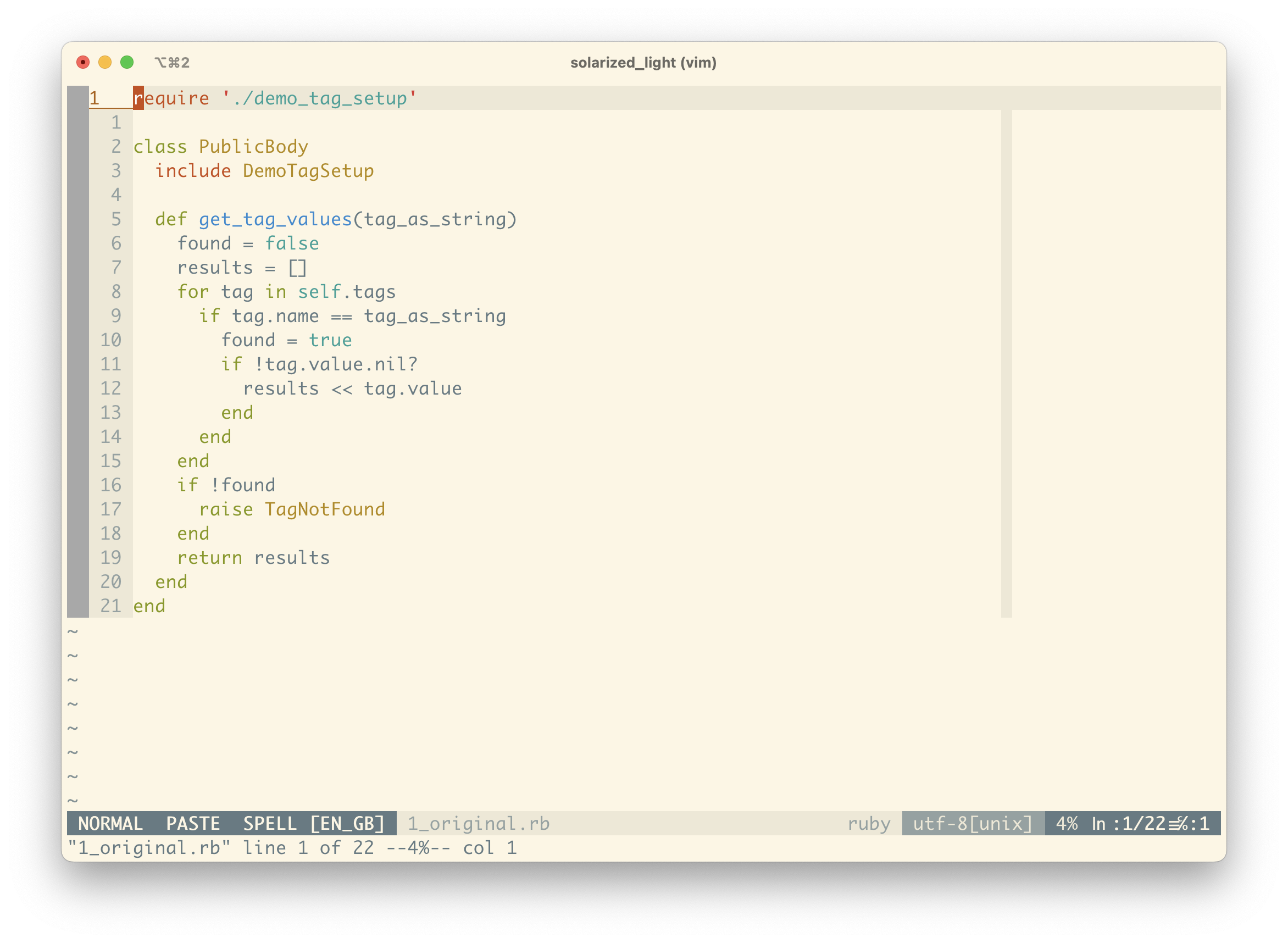

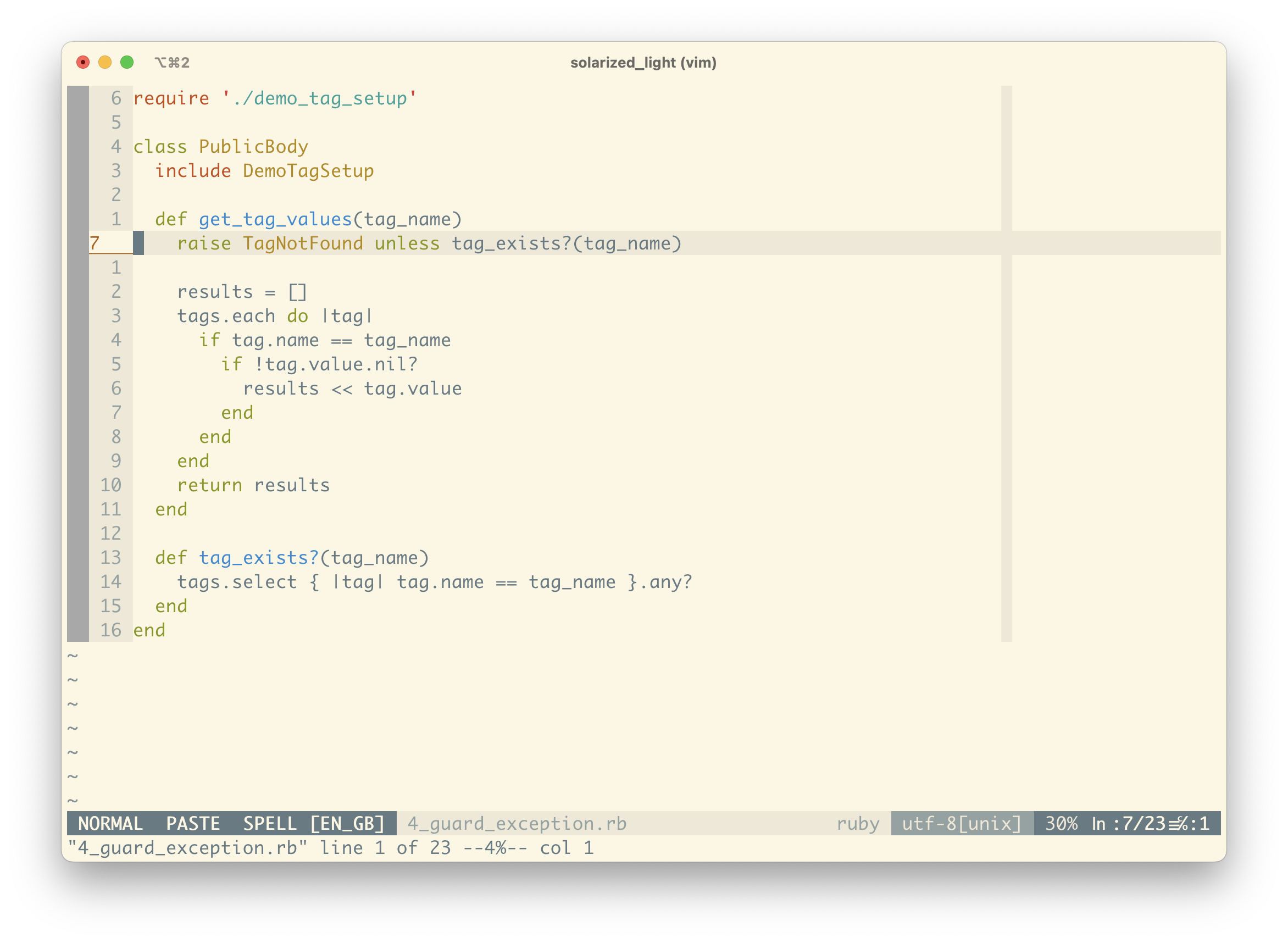

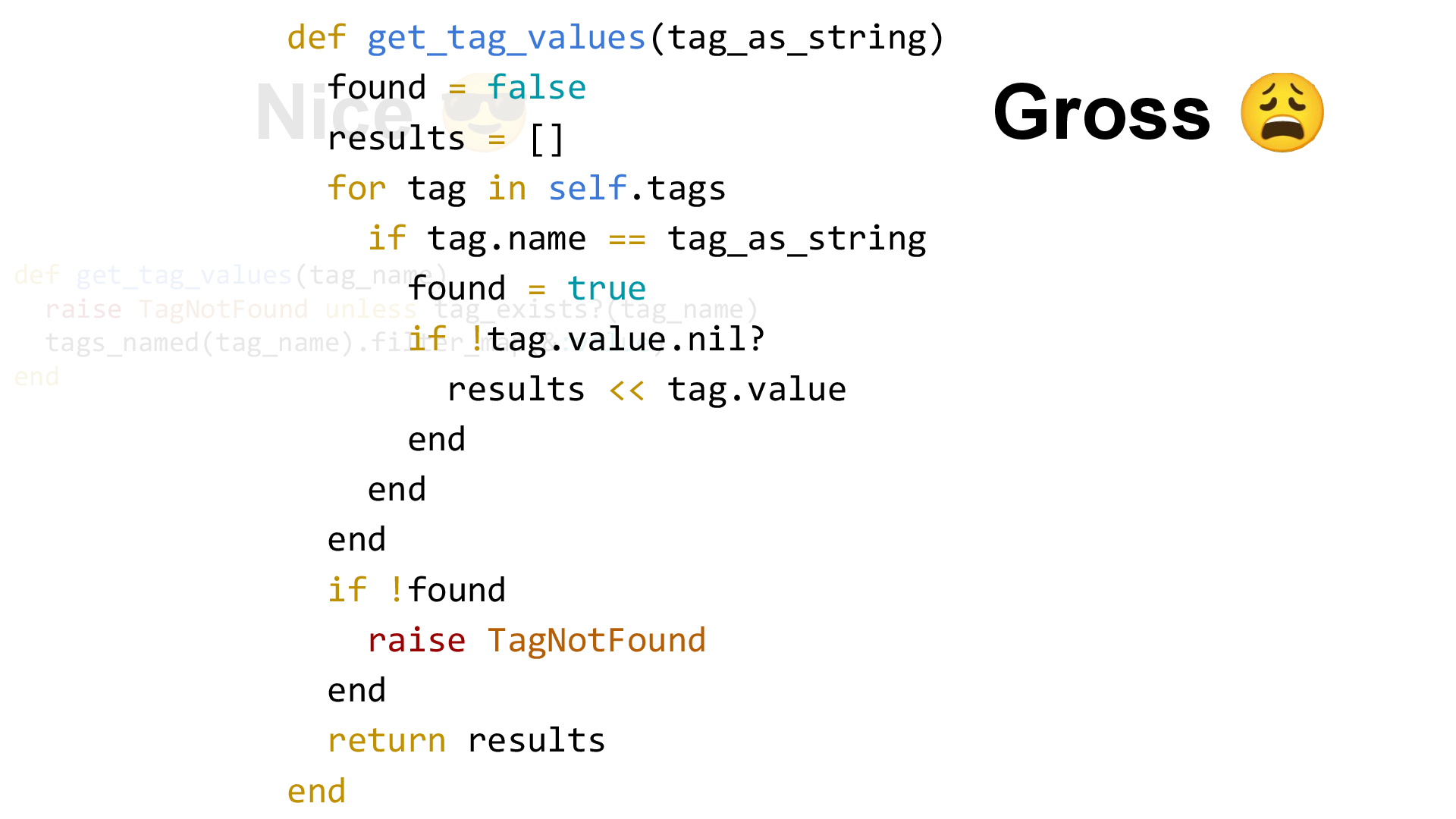

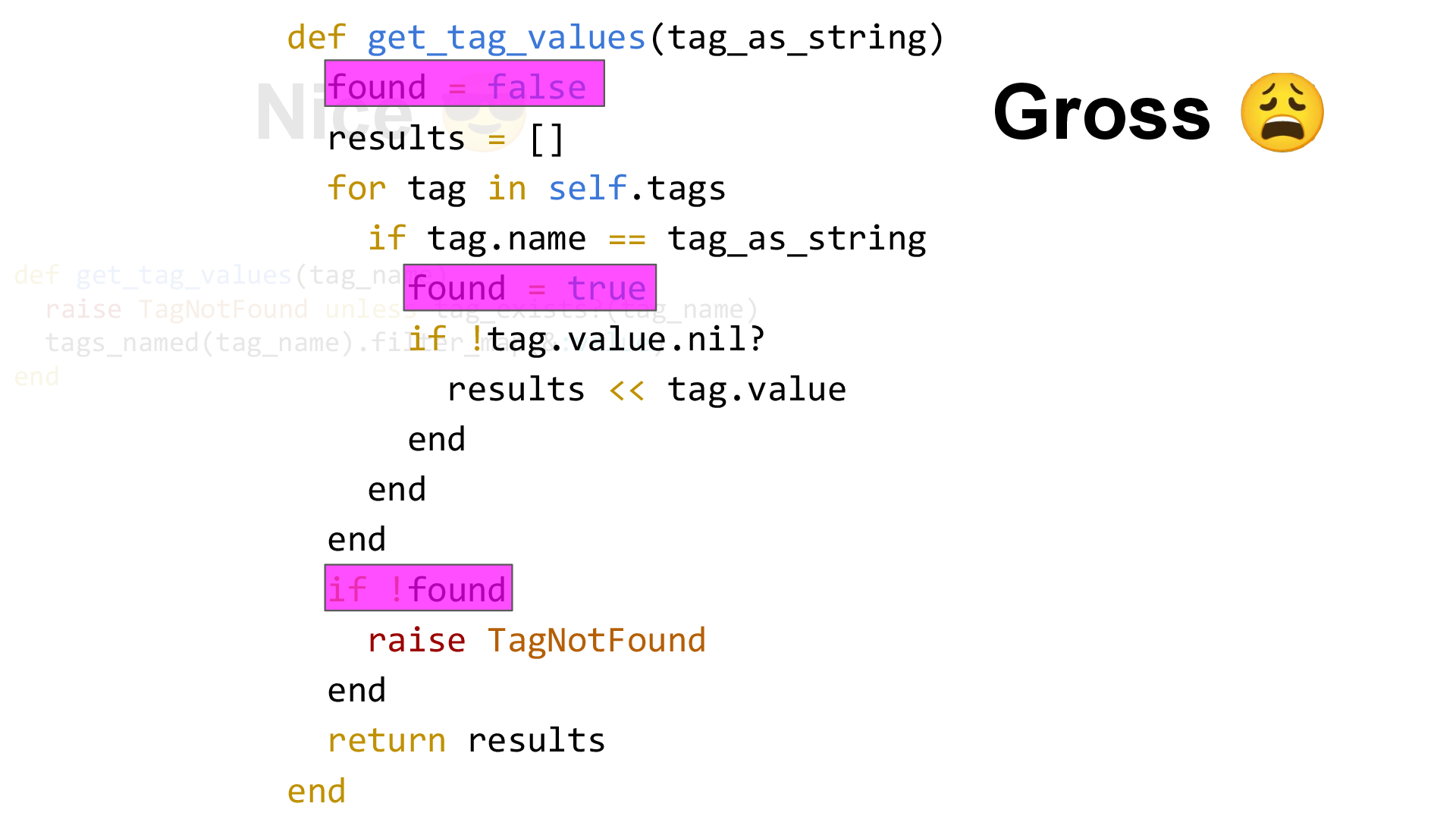

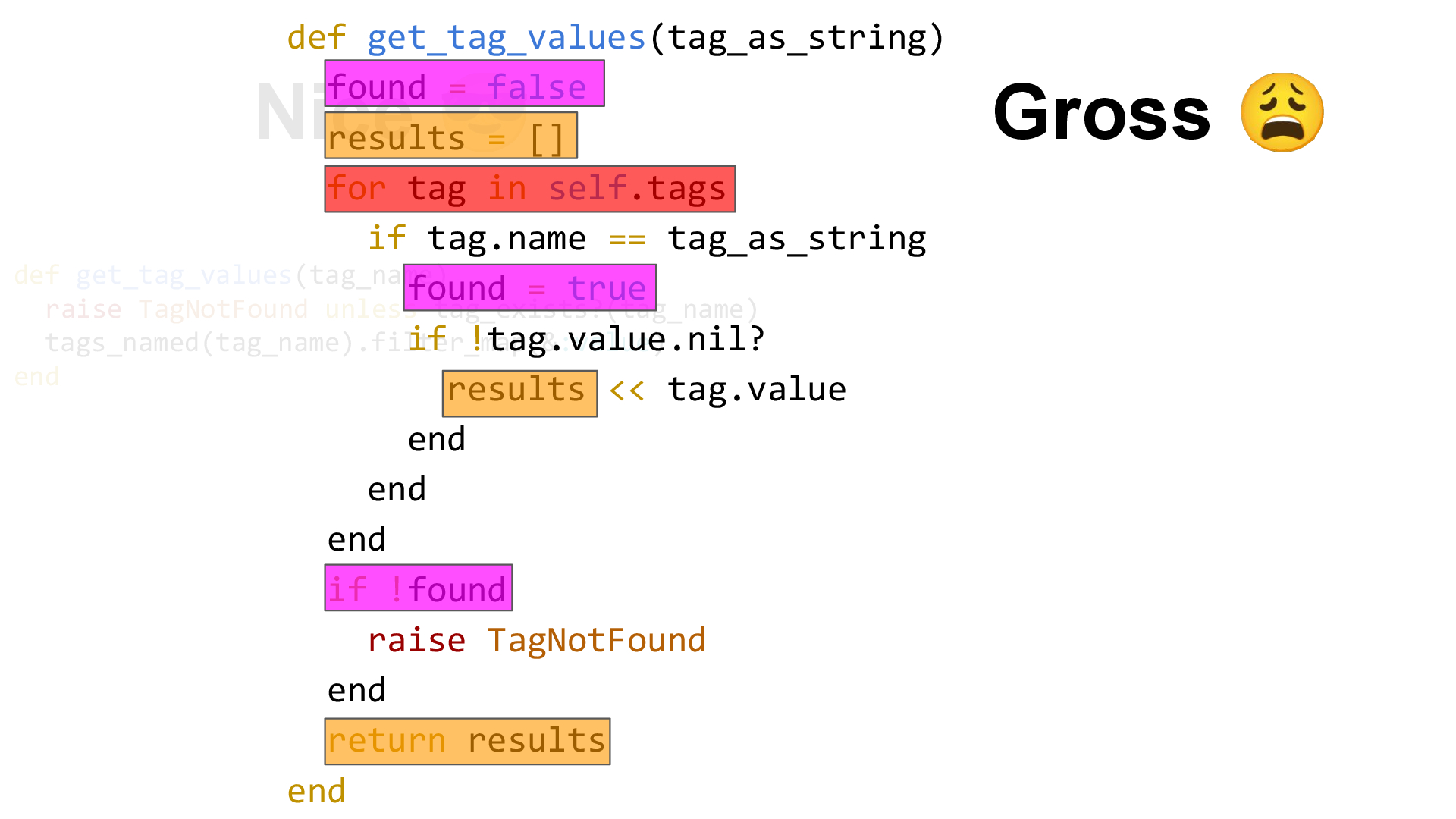

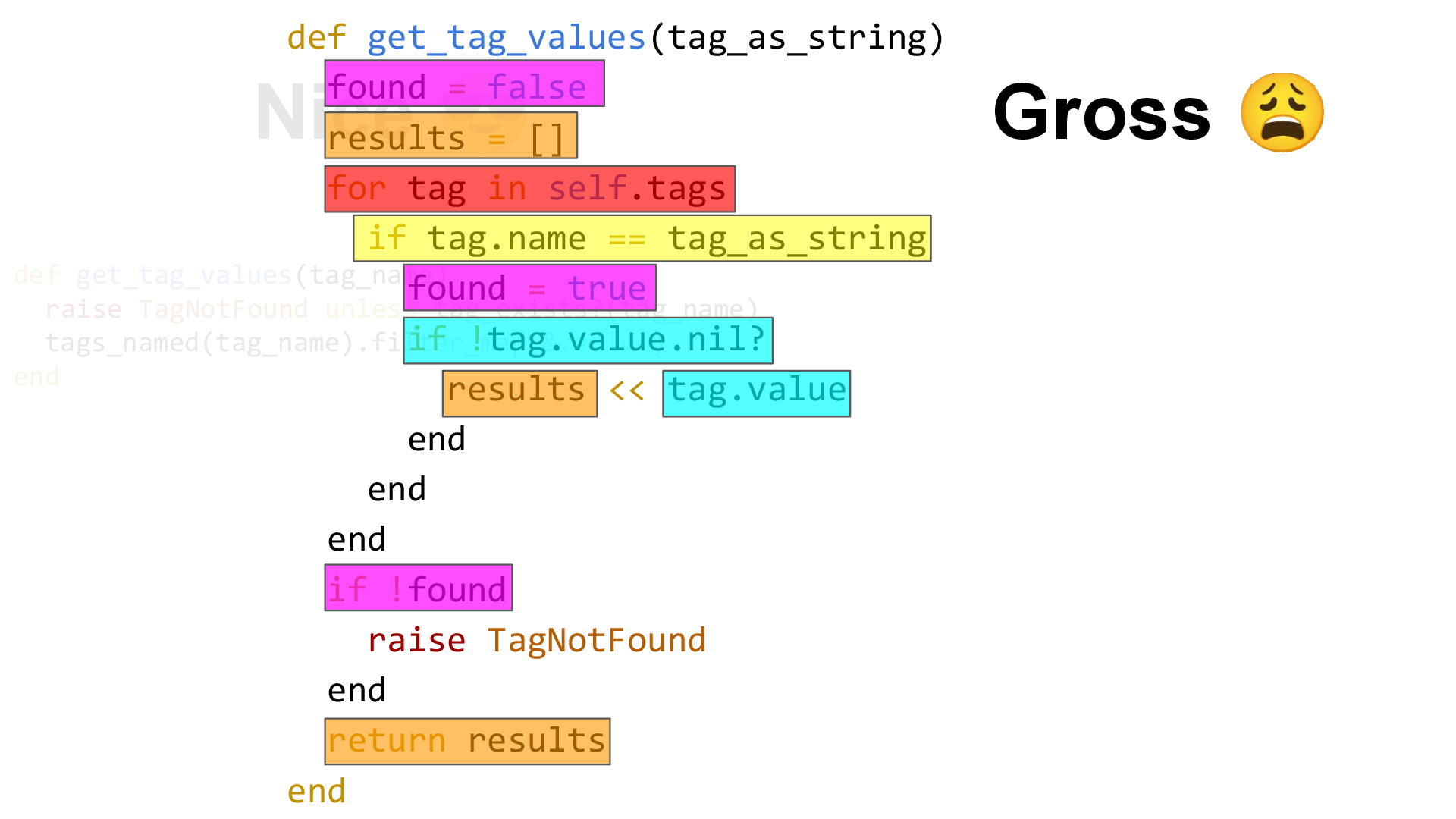

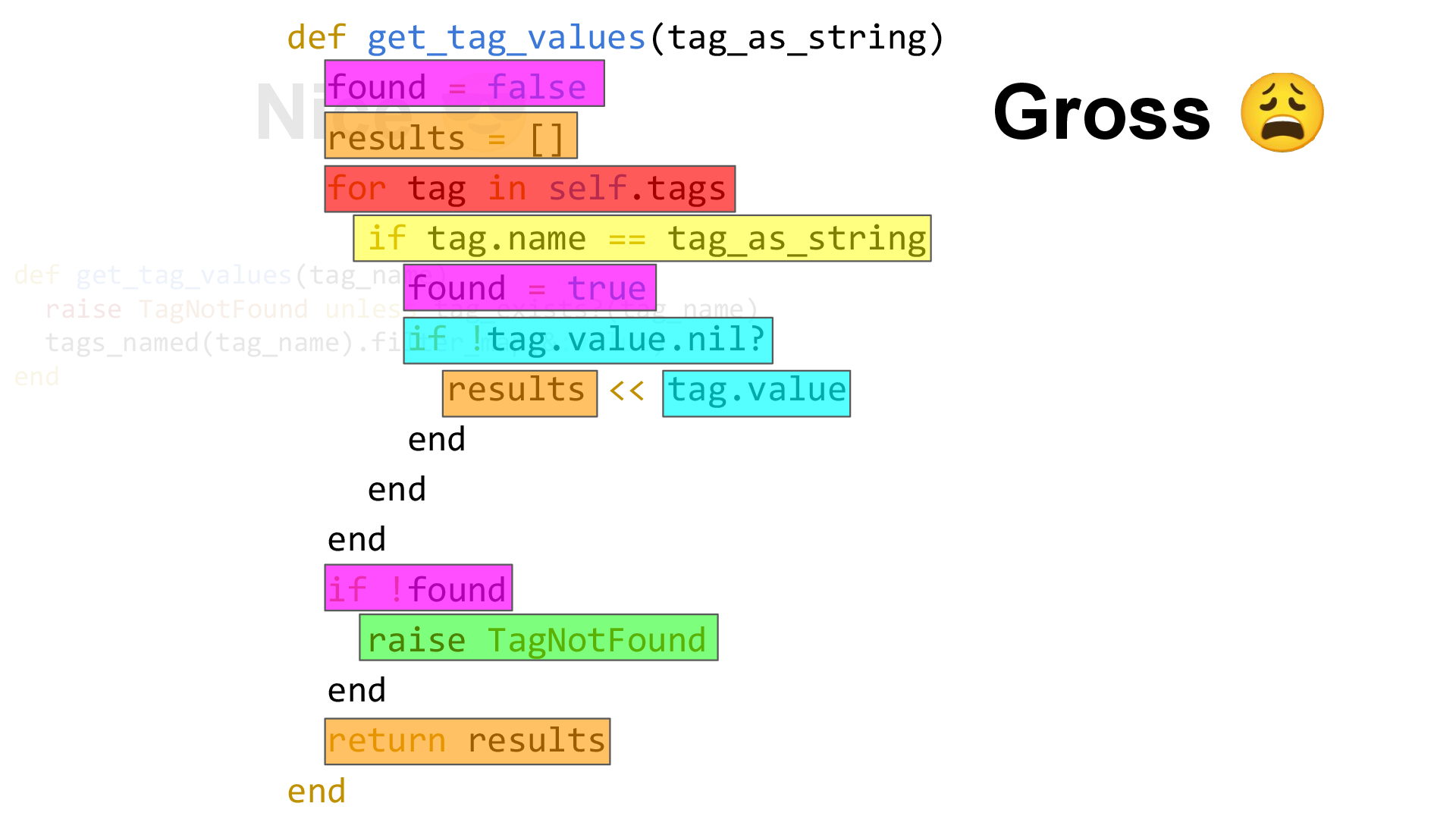

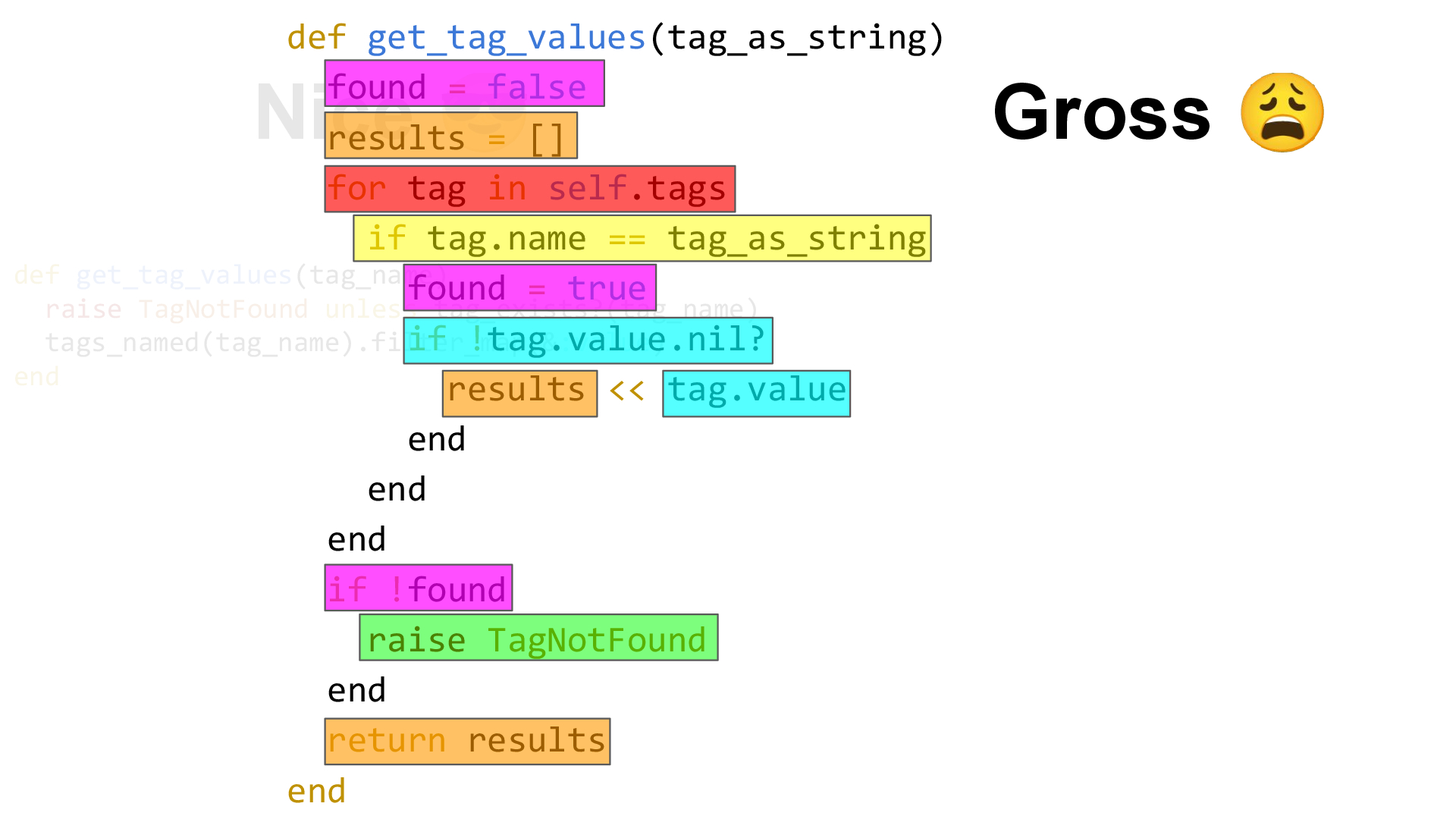

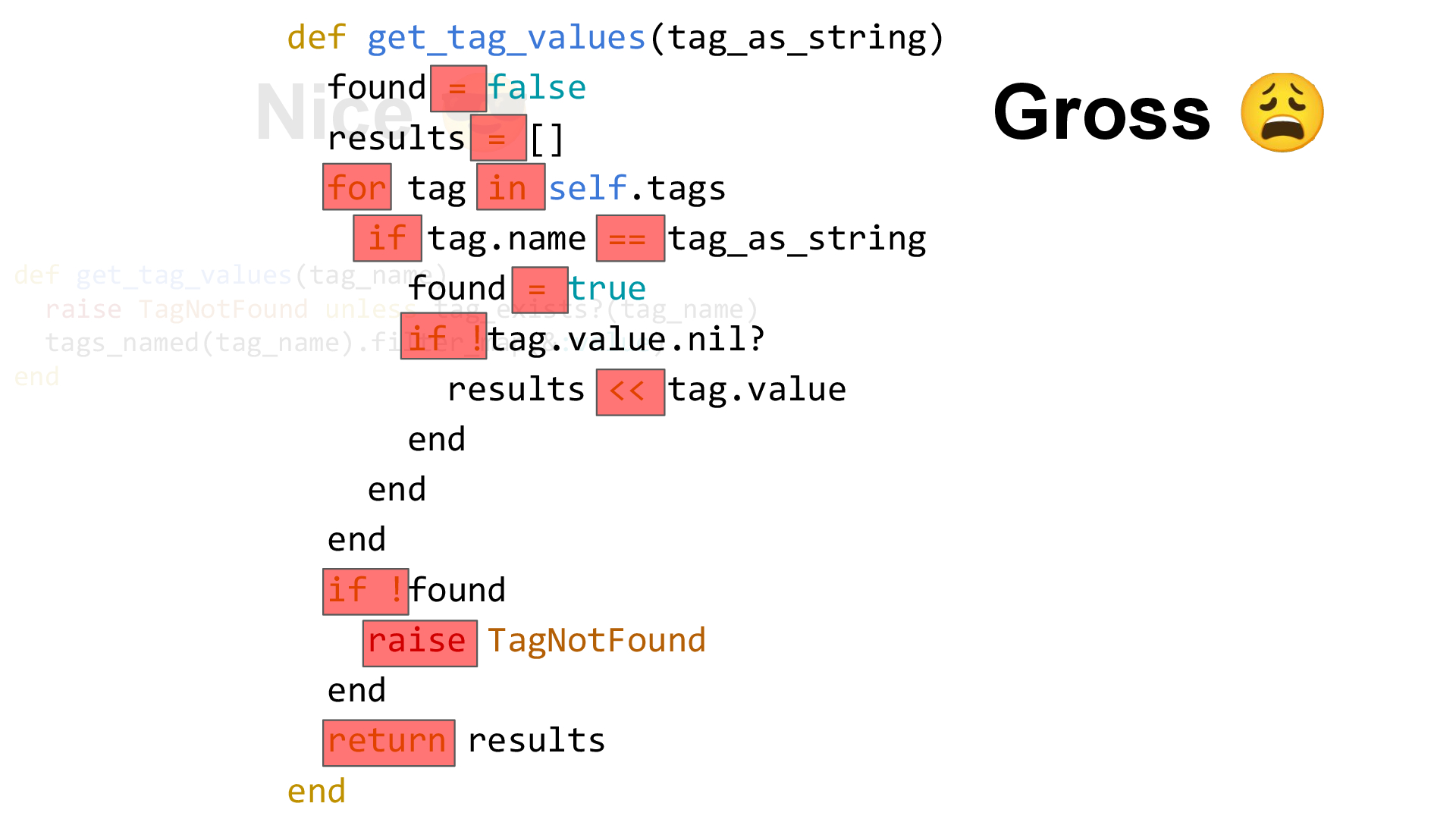

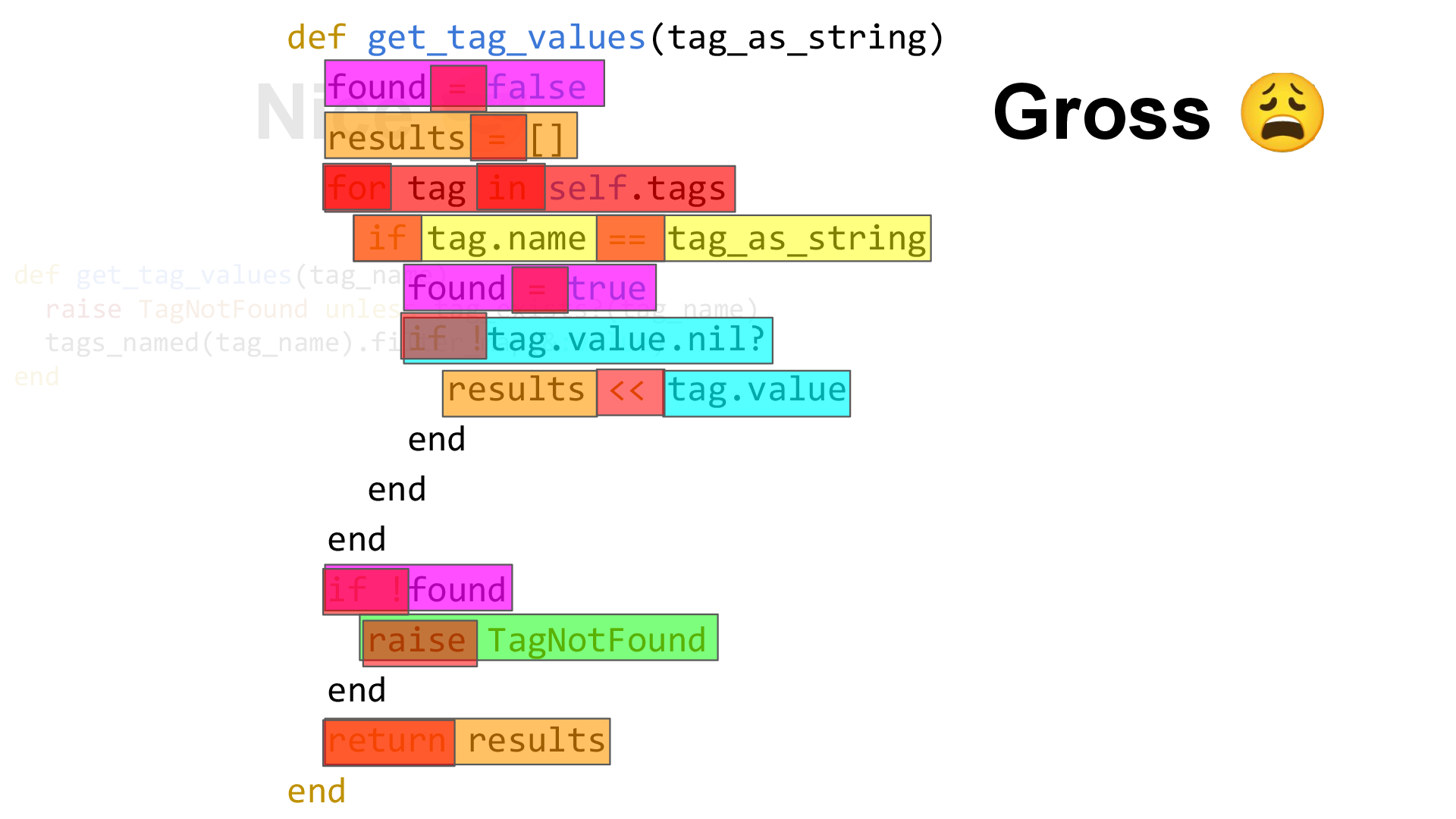

This is another example from the Alaveteli codebase.

What does this do?

I can tell you it works. This code is probably running right now as we speak.

But for me to really understand exactly how this method works, I’d have to spend a minute or two concentrating on it line by line.

It might not sound like much – a minute or two – but Alaveteli has around 30,000 lines of code. The more complex each of these methods is, the harder it is to understand larger chunks of the system at the same time.

Let’s see what we can do to make this clearer…

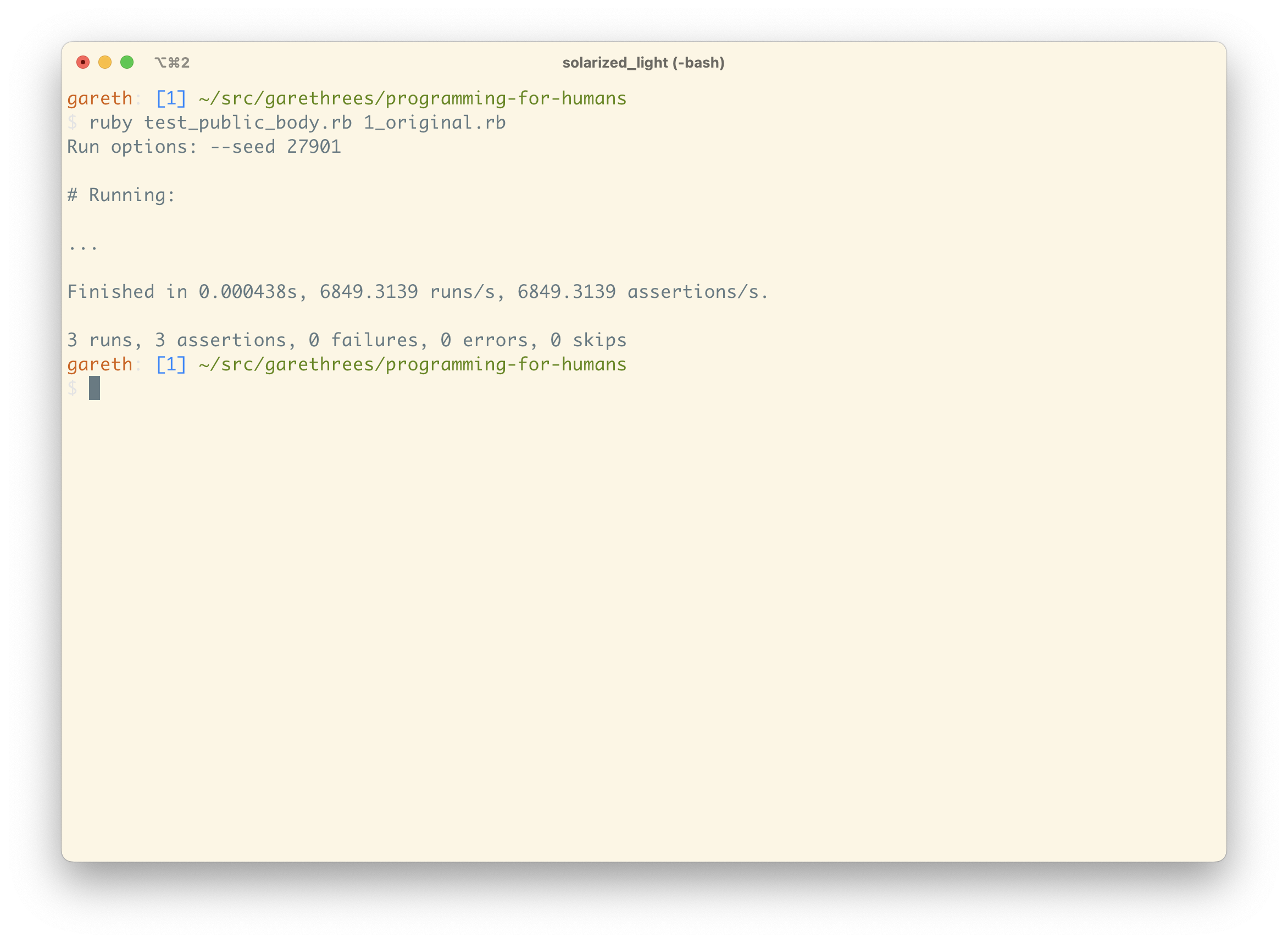

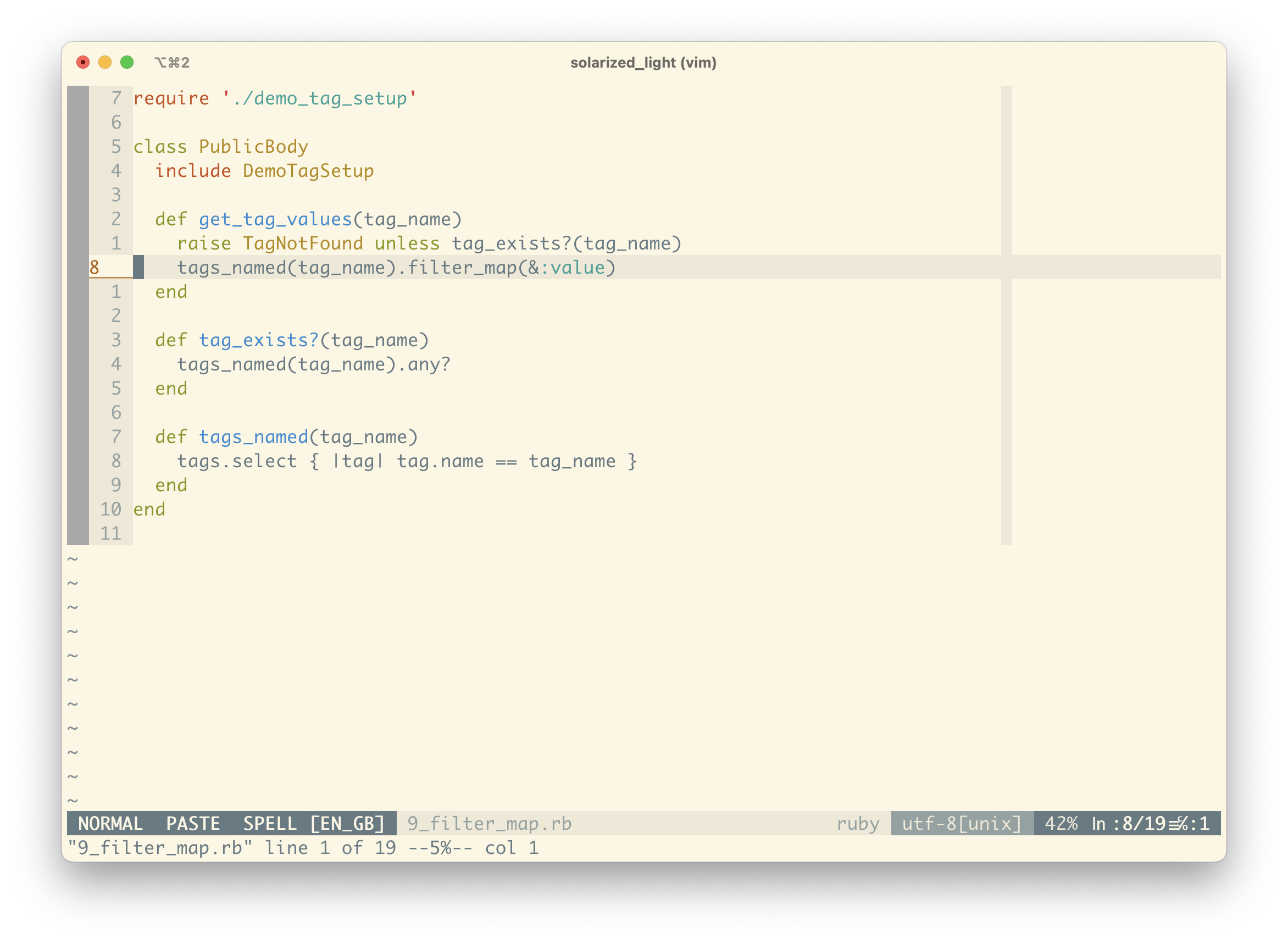

I’ve extracted out this get_tag_values method to a separate file and stubbed out some test data so that it’s a bit quicker to work with for this demo.

I’ve also created a little test suite so that the functionality stays the same after each change.

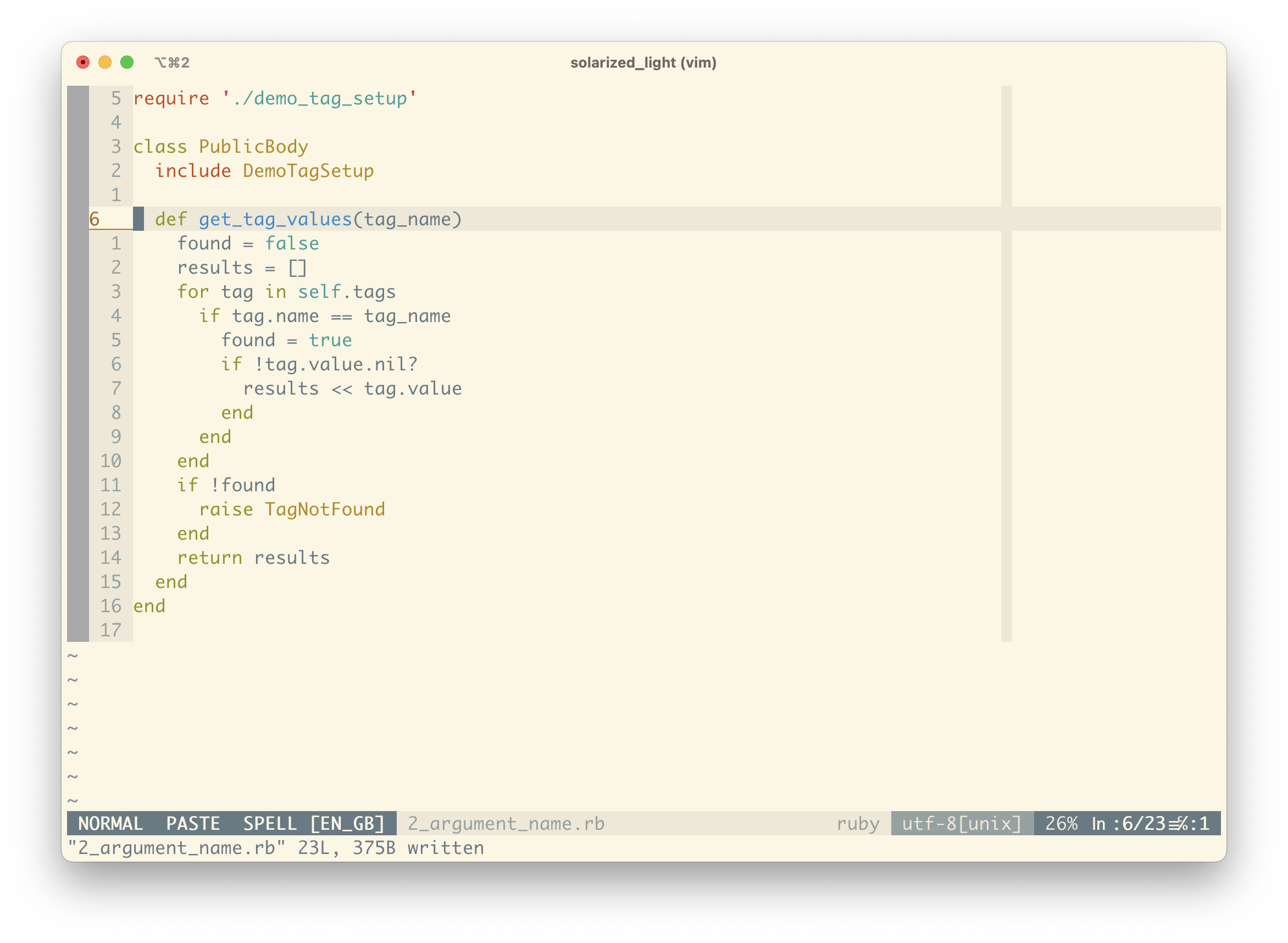

The first thing I’m noticing is that the argument name “tag_as_string” isn’t quite right. In our case, a Tag can have a name and an optional value. Given a tag with a name and value, when we say tag_as_string, we’d represent this tag as foo:bar (name:value) when converting to a String.

This method doesn’t handle splitting the name from the value, so what it actually accepts is a tag name in String form. As such, let’s change it to tag_name.

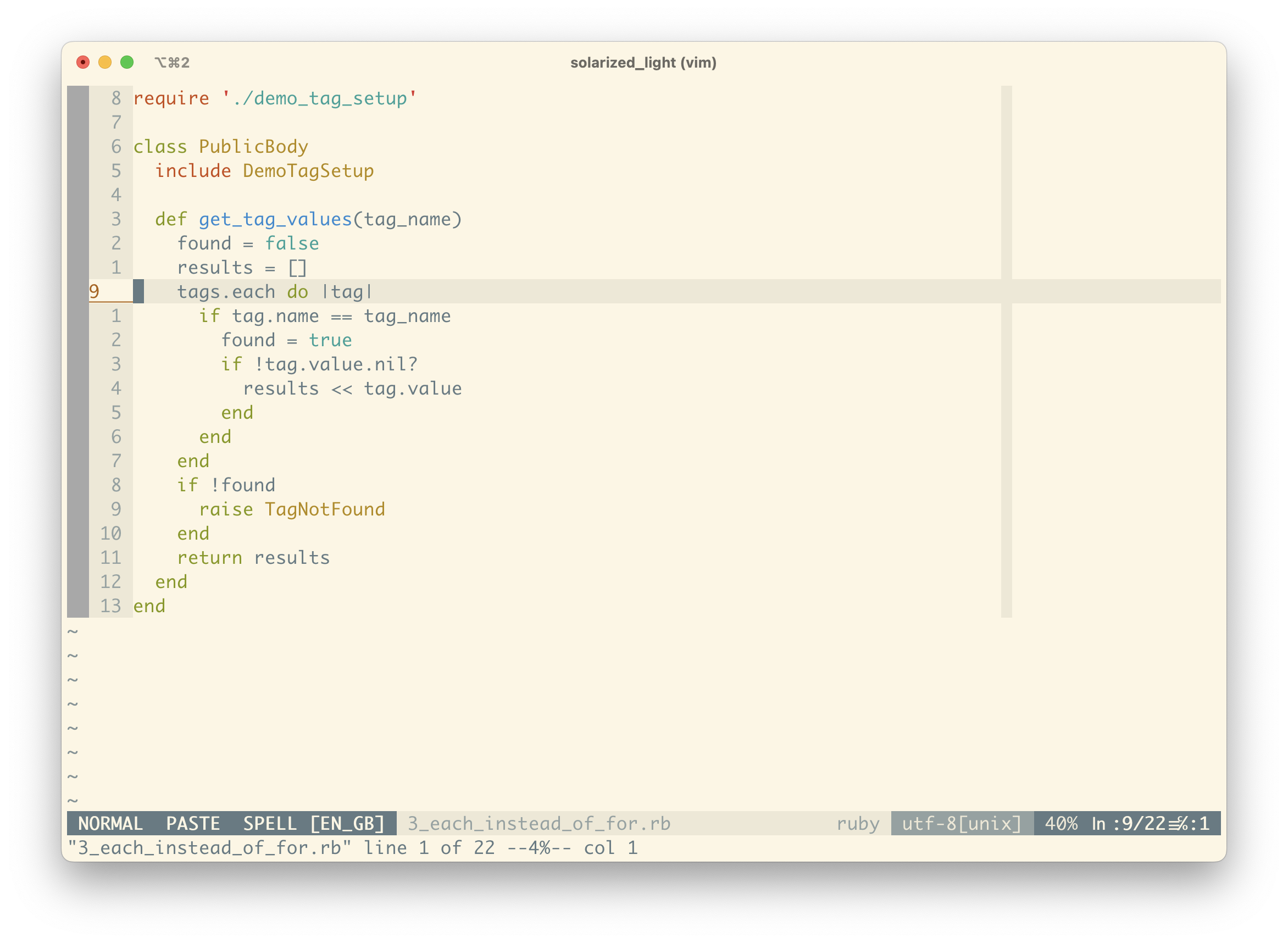

The next thing that sticks out at me is the use of a for loop. It’s a bit much detail to get in to here, but most of the time in Ruby we use iterators like each. There are some specific reasons you might use for, but we’re not doing so here, so we’ll change to an each.

We can also remove the explicit self as Ruby figures that out for you in this context.

We’ve cleaned up some basics, so now we need to really start looking at what’s happening in the current code.

The most obvious thing to me is the handling of a non-existent tag. Usually we use a guard clause to check for invalid data, so this feels like a good place to start.

It looks like we’re looping through all the tags associated with the PublicBody instance, and then comparing their name attribute with the tag_name argument passed to the method. In other words, we’re raising an error unless the tag exists in the list of associated tags.

It seems like we can encapsulate this filtering in a method – tag_exists?. We’ve introduced some duplication, but we can clean that up shortly, and it’s allowed us to write a really clear guard clause.

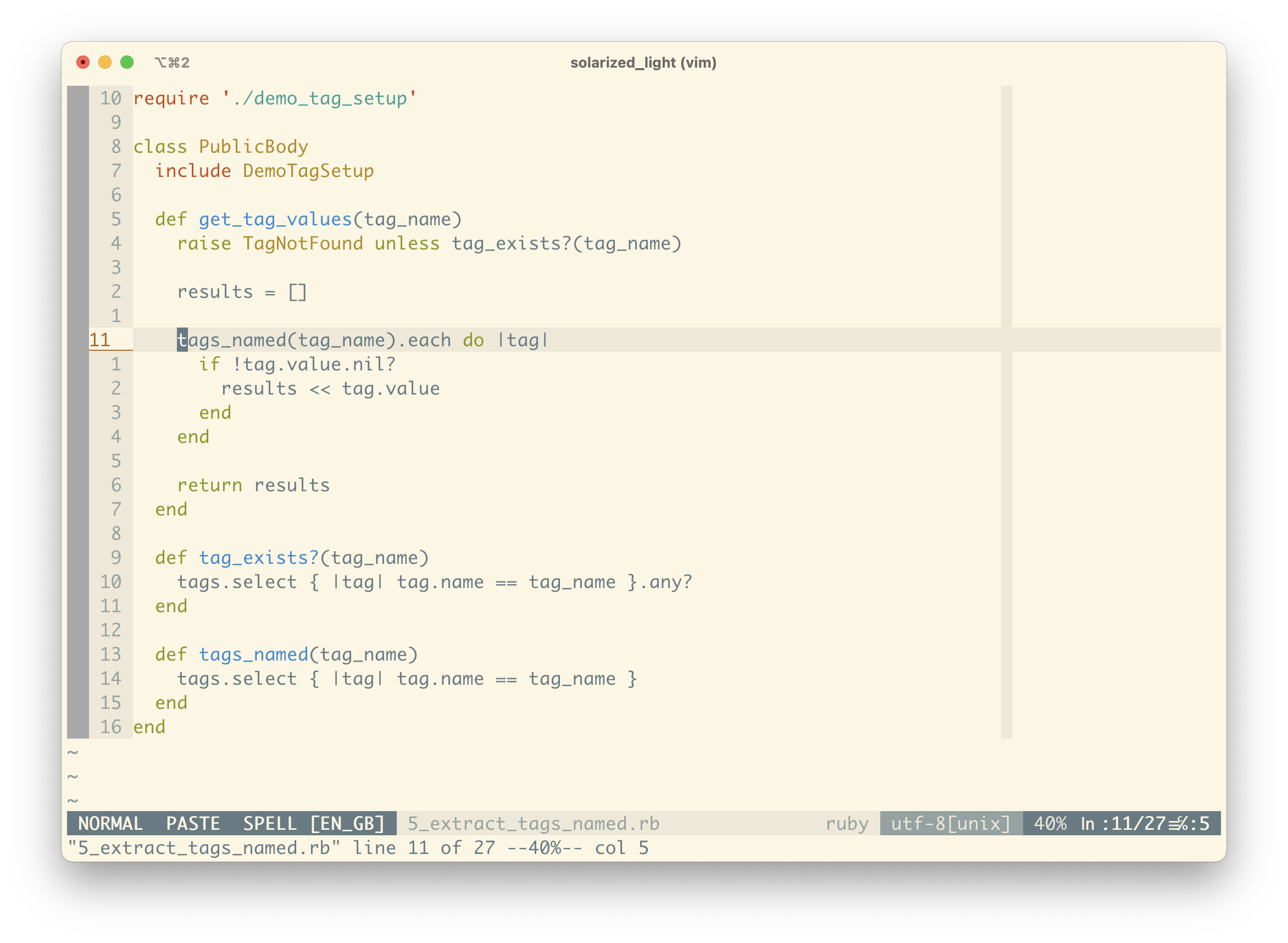

Now we’ve handled the edge-case of being given an invalid tag, we can look at the bones of handling extracting values of a valid tag name.

Remembering the logic from before – iterating through each associated tag and comparing by name – we can extract this filtering step so that we only check the values of tags that match the given tag name argument.

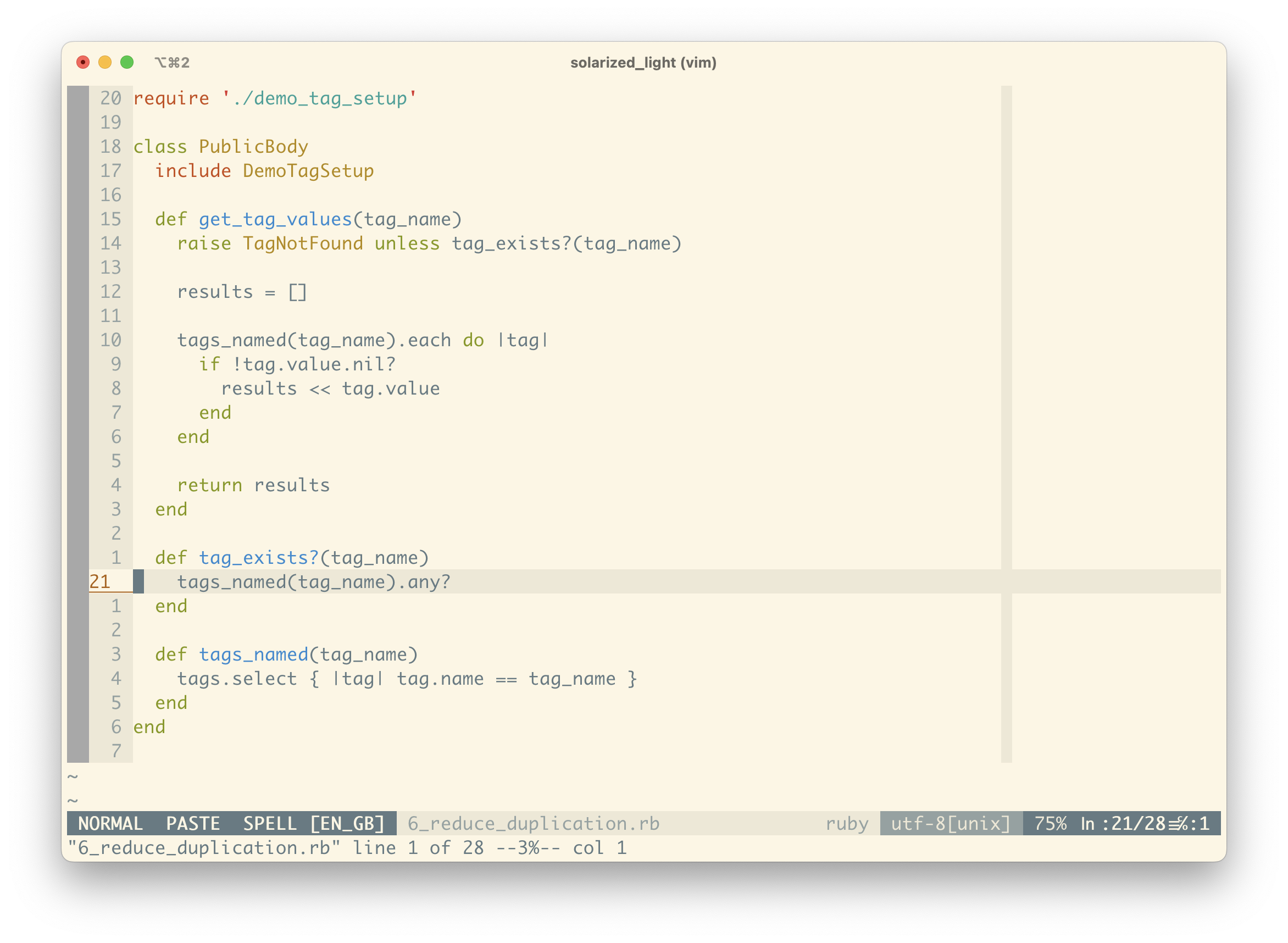

The previous step introduced tags_named, which in implementation looks nearly identical to tag_exists?. We can now re-implement tag_exists? in terms of tags_named.

Notice how we’re pushing the details down so that our higher-level methods are quite readable in human terms. Most of the time we won’t be needing to remember exactly how we find tags with a given name; we’ll take it as a given. It’s much easier to understand that tag_exists? checks for any tags_named “foo”.

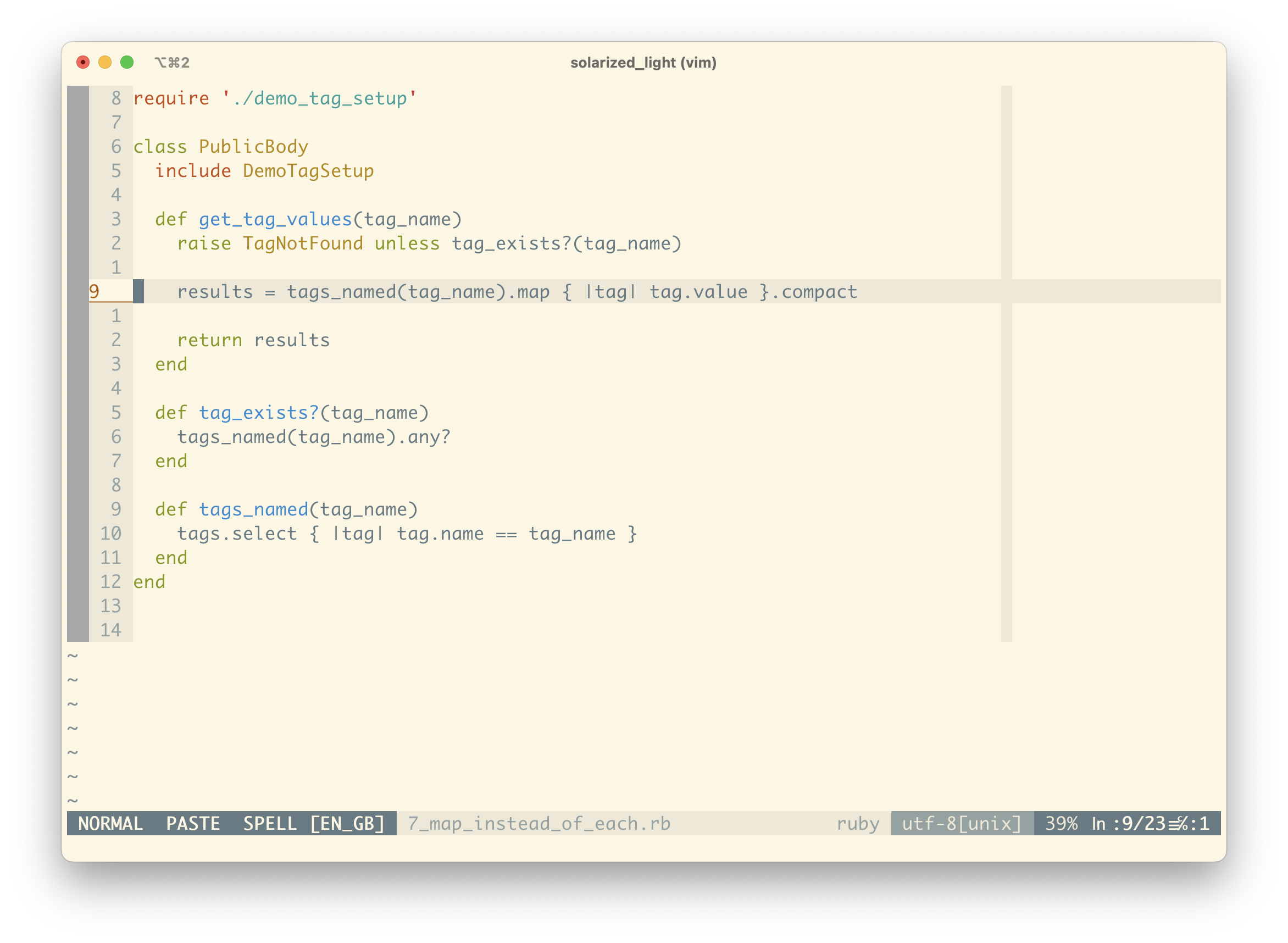

We’re on the home stretch now! The method is reasonably clear, but each time we read it we’ve still got to figure out what the innards of this loop is doing.

For the relevant tags, we’re checking whether they have a value and if they do, we’re storing that value in a “results” collection. This isn’t terrible, but it still takes a bit of work to comprehend.

Instead of manually constructing our results Array we’ll use a map, which handles this internally. Now we can focus on writing only the domain logic that matters to our application – collecting all values from the tags that we iterate through into an Array.

That takes care of extracting the value, but we need to remember that we’re not interested in nil values. To handle that we can just compact the Array returned by the map. compact just removes nil values from an Array.

You could argue that this is being “too clever”, but map and compact are bread and butter in Ruby, so while there is a small learning curve for a newcomer to the language, we’re not doing anything particularly esoteric.

I’m feeling pretty good about the code at this point, but there’s still a moment of hesitation as I figure out what we’re mapping over. Instead we can use another common Ruby trick to make the intent even clearer.

Instead of a block ({ |tag| tag.value }) we can use the proc shorthand when the called method is the only operation of a block. Now it’s much clearer that we’re “mapping the values” – map(&:value).

We can also get rid of the temporary results variable, since Ruby automatically returns the result of the last operation.

Finally, we could use a newer built in Ruby method called filter_map, which does the map and compact in a single step. This is a little less common, but it’s no different to how we pick up new words and concepts in natural language. We used to say “The World Wide Web”; now everyone knows what you mean when you say “the Web”.

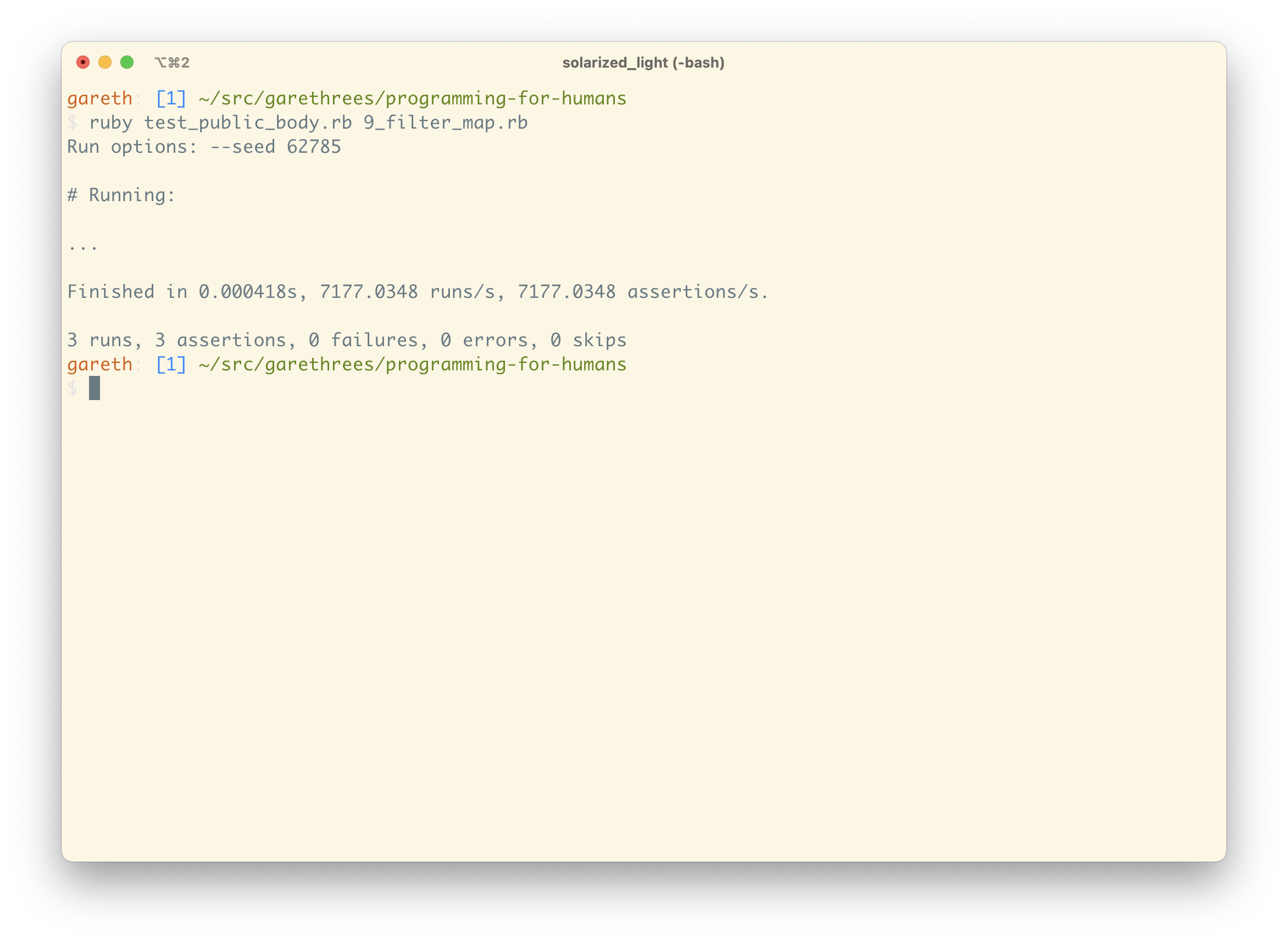

We’ve been running our tests after each step, and one final run shows our method still working as we expect.

Why does all this matter?

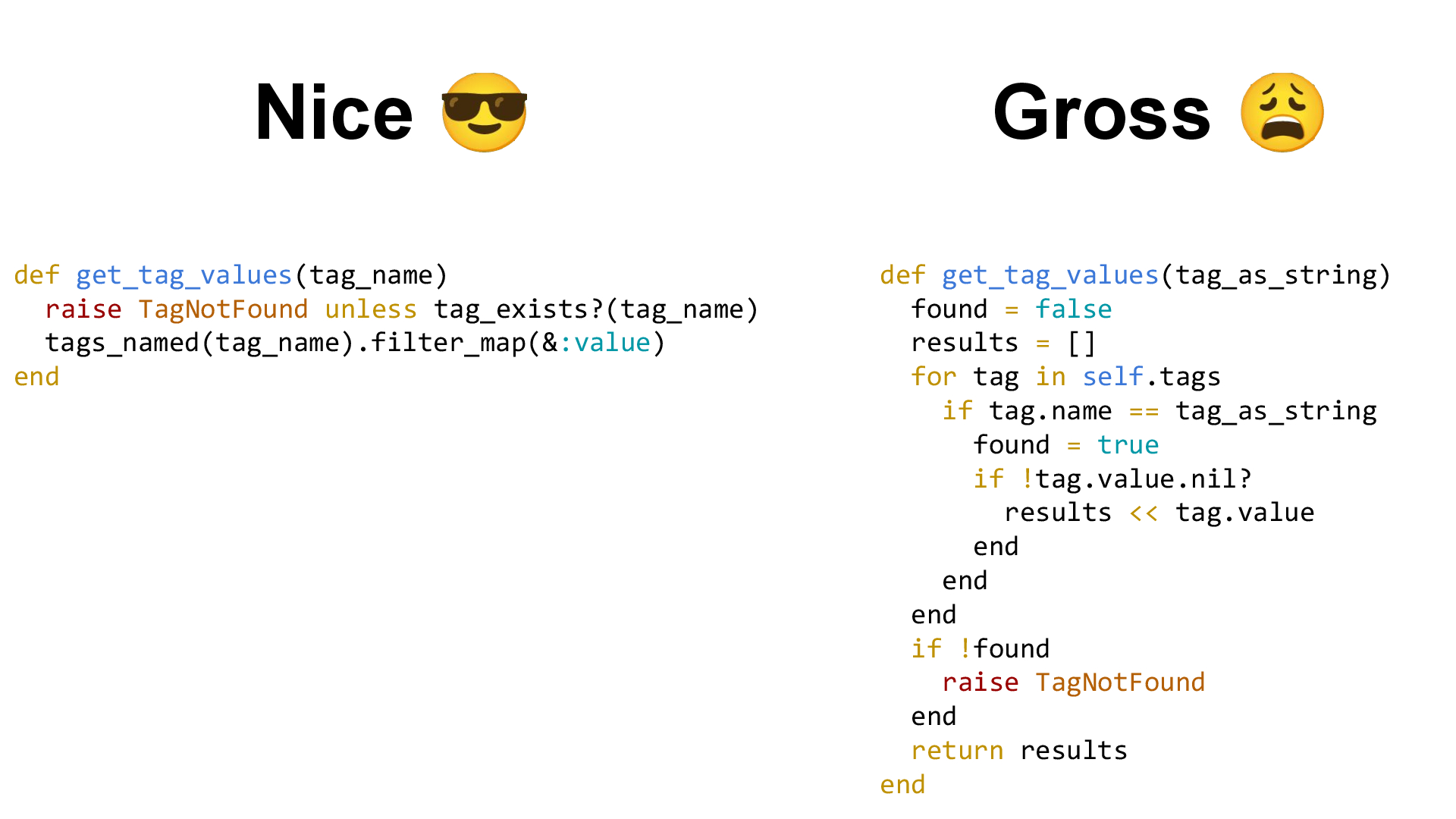

Think of the effect of trying to work with thousands of lines of the gross version every day.

It’s like working in a dump…

And that’s why it feels like this.

Our brains can only hold around 7 things in our head at any one time.

Which is why, for most of our work, we need to optimise our code for humans to read.

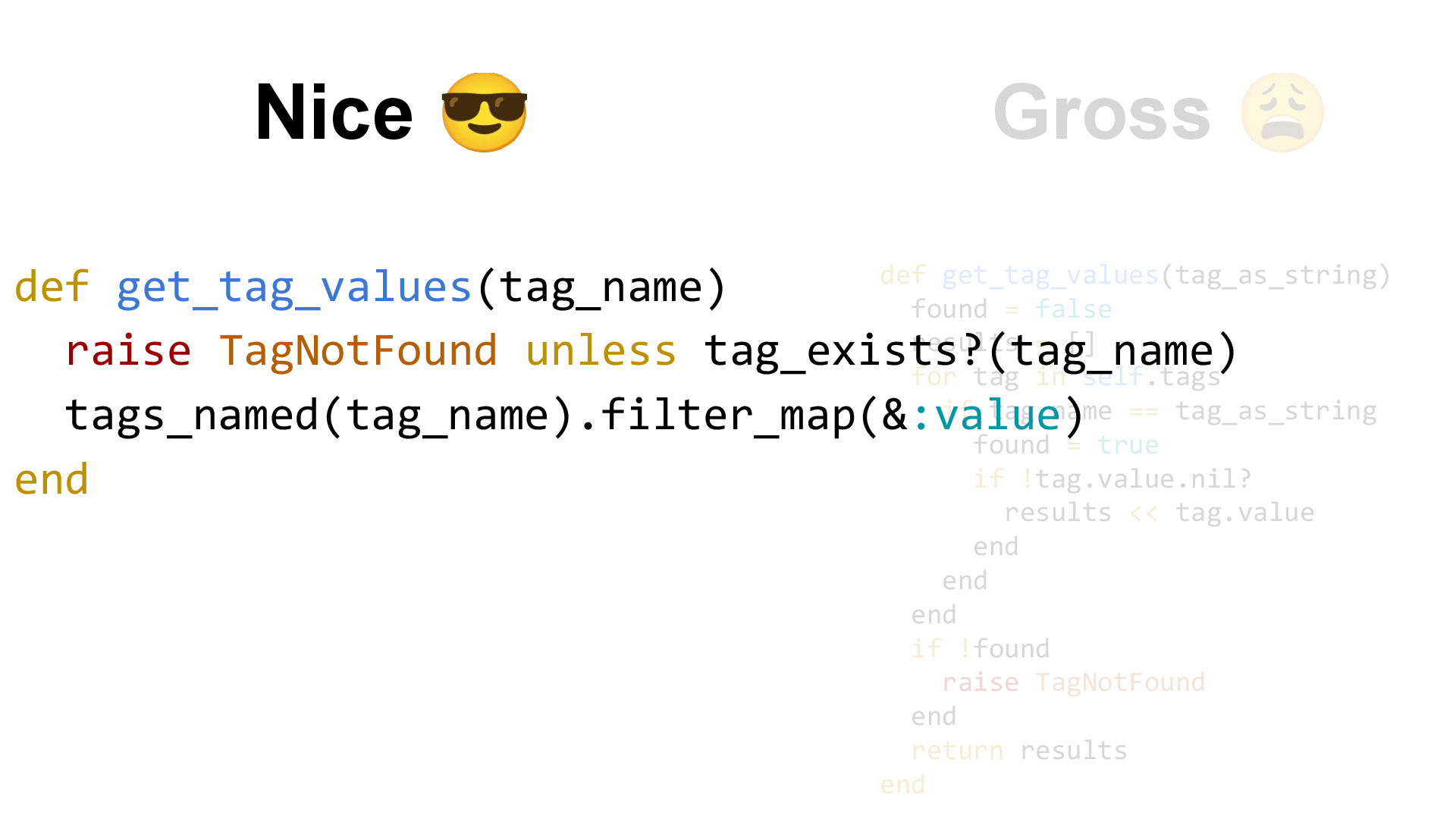

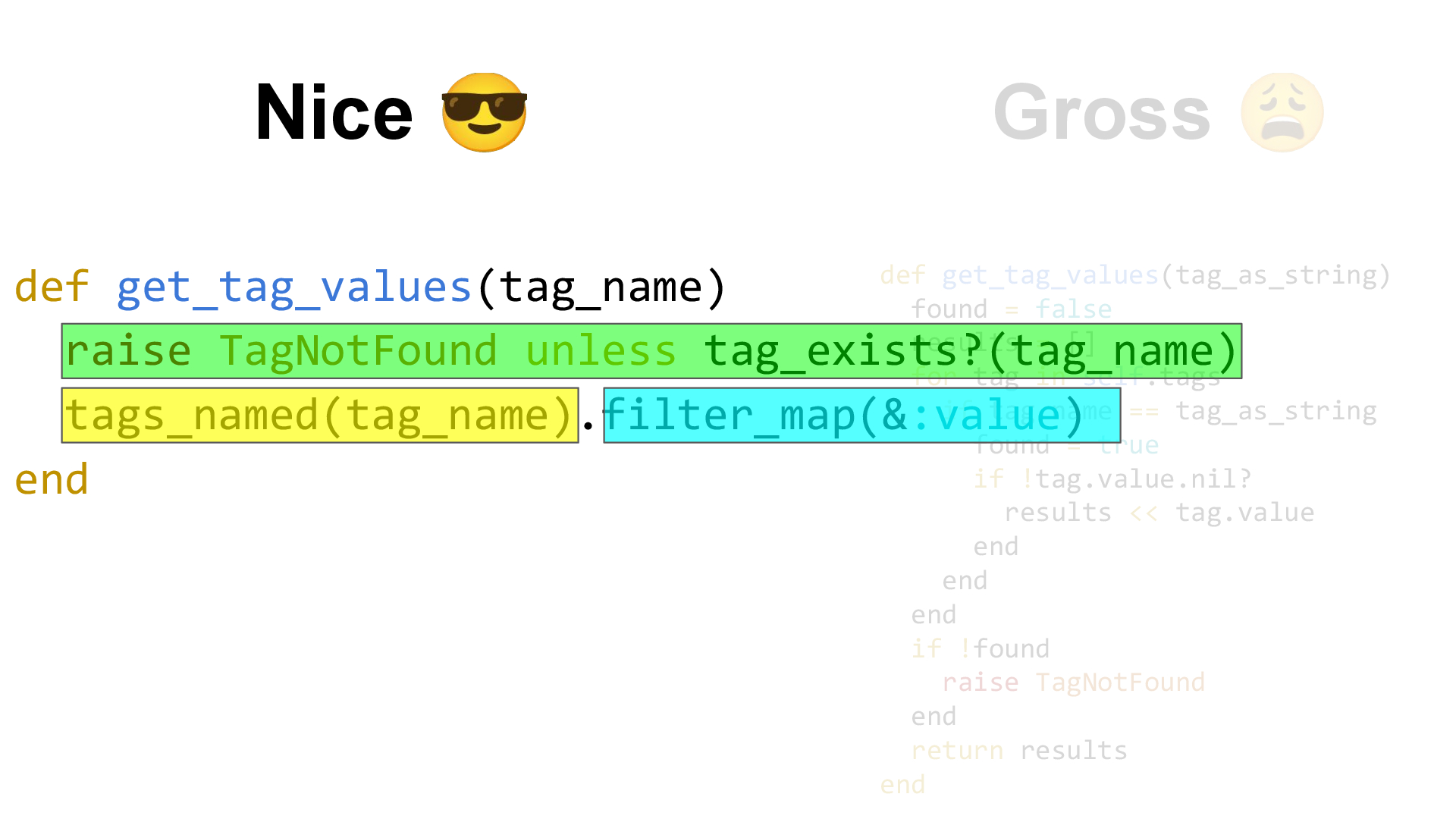

Look at the language and the number of concepts in this version.

Here, we’ve only got 3 concepts to worry about.

- Raise an error unless we know the tag exists

- Find all the tags where they have the given name

- Collect any values for the tags that have them

Let’s contrast that with the previous version.

This has at least 6 concepts, depending on how you count.

1. The idea of this “found” variable

2. A collection of results

3. Some idea of a group of tags that we’re looping through

4. A comparison between the input variable and the tag name

5. Some figuring out over whether to add the tag value to the results collection

6. Then we’ve got the idea of raising an error message if we couldn’t find something

Being 50% more complex is bad enough on its own, but look how each concept is sprawled all over the place.

Each line you read is to do with something different than the lines around it.

There are also more “moving parts”.

Each of these language operations have an effect on what’s happening

So when you actually try to read this, your brain literally cannot process it as a single idea.

You’re forced to read it in chunks, skip up and down it, and all this becomes really mentally draining.

And that’s why it feels like this.

Look familiar?

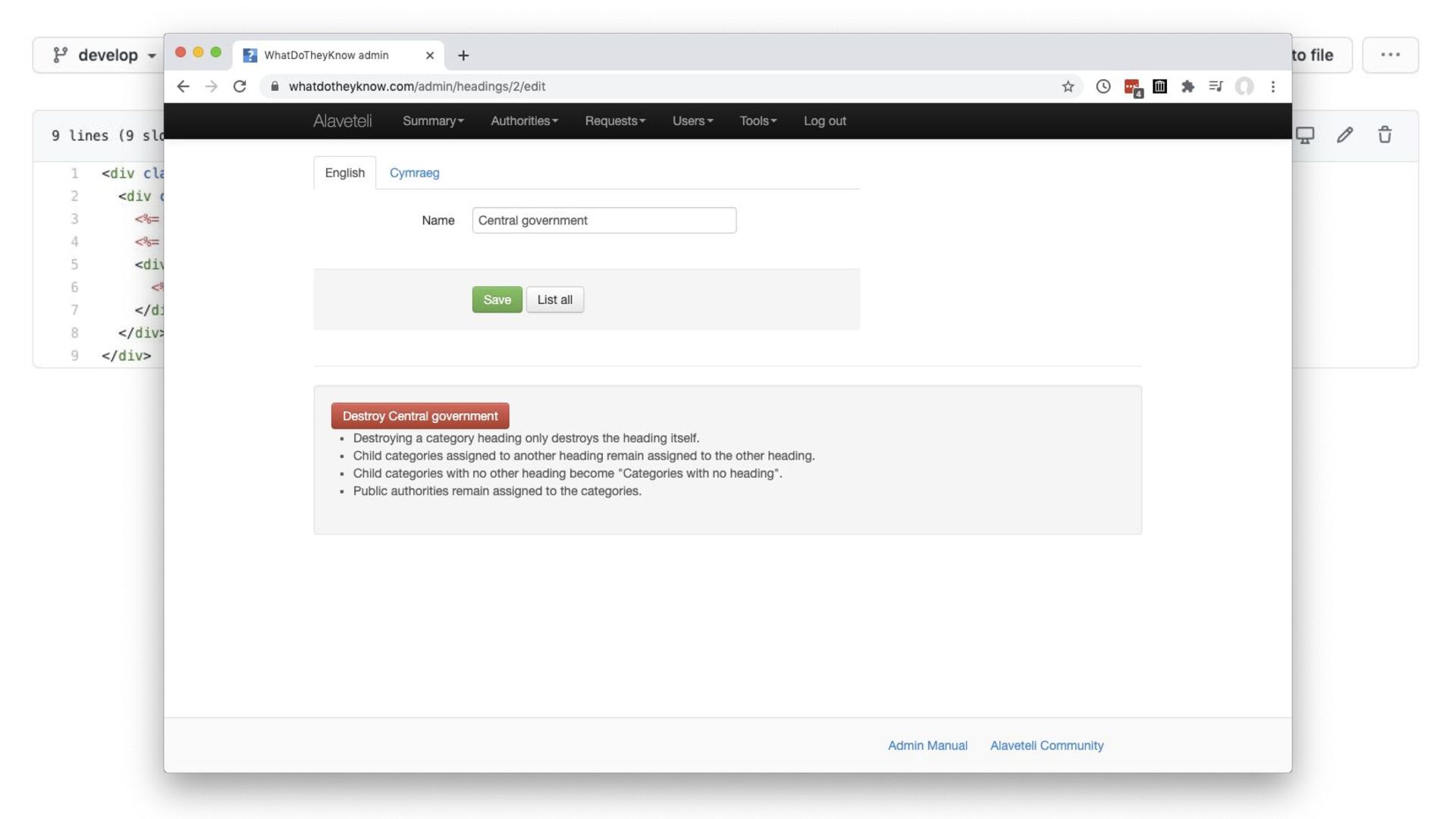

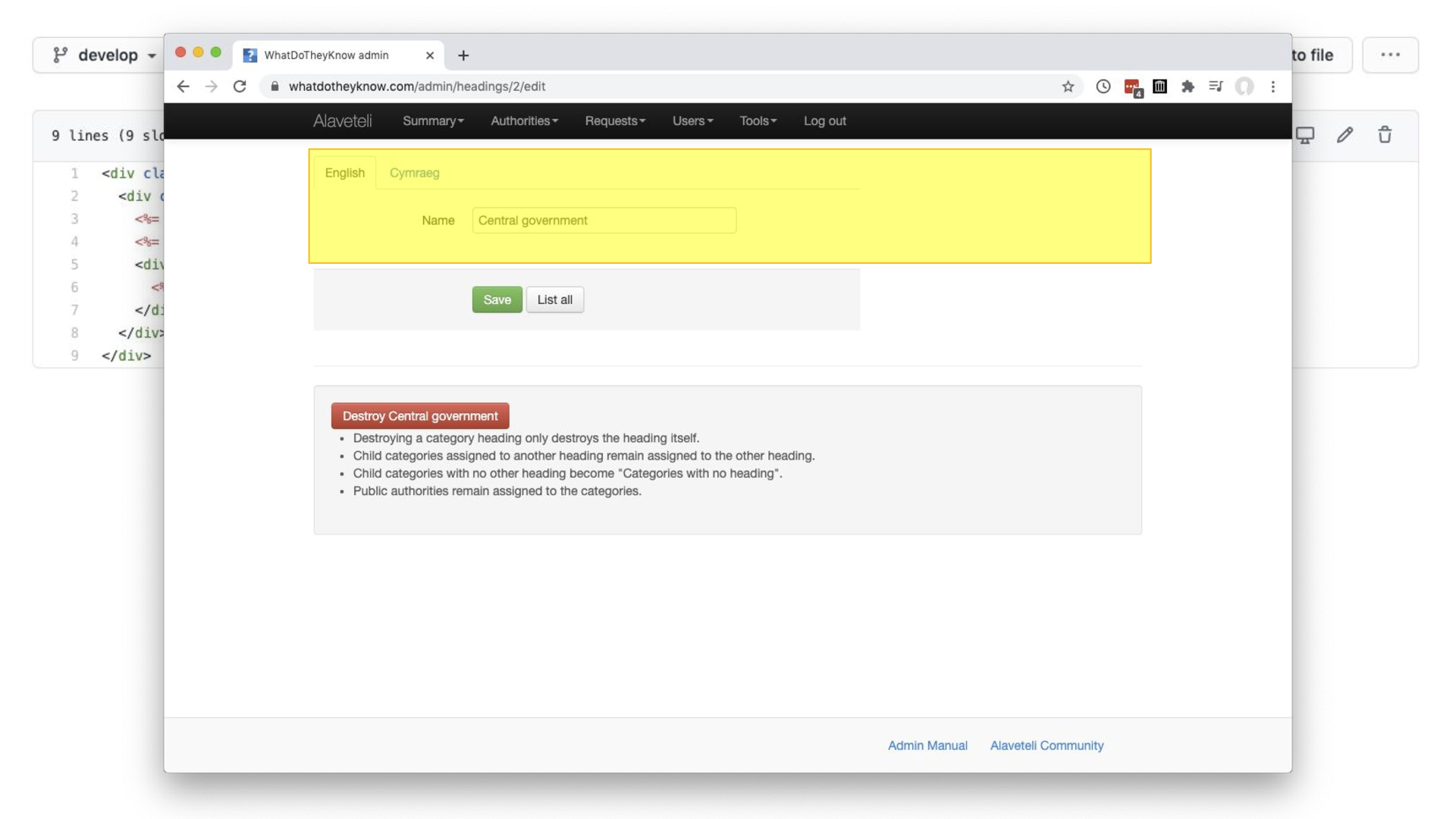

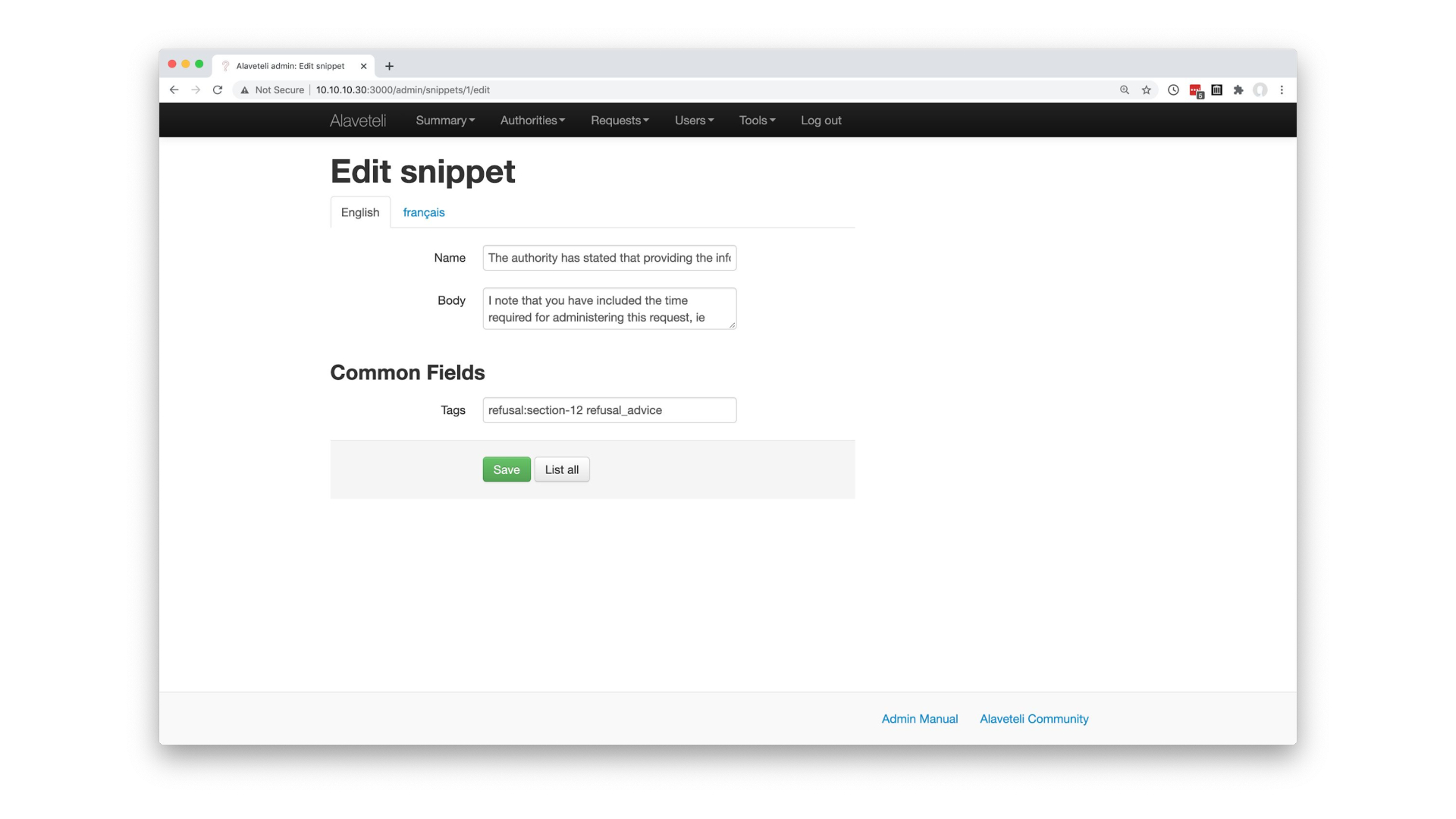

We’ve been working on a project to add some snippets of text to help our users challenge refusals to their requests for information. To manage these snippets we need an admin interface.

Before I started working on this I was thinking “oh, we’ve already got translated forms; shouldn’t be too hard to basically copy and paste”.

And then I opened the code and encountered the code I showed at the start of this talk. With enough time I figured it out, sure, but it’s pretty frustrating to re-work code like that.

It took me the best part of a week to reduce the complexity of the original code and then add the new admin form with this much clearer code.

If we’d have spent the time to make it clearer when the code was first added it would have taken me far less time.

I could have spent that time doing more important things that help our users, or at least being less frustrated if nothing else!

And it’s not just you that complex code affects. It’s your team when they’re trying to work with your code and people who work on the code long after you’ve moved on.

One of the most valuable things you can do as programmers is develop an eye for clarity.

If you want to be a good photographer, you’ve got to look at a lot of pictures, take a lot of pictures and critique them to understand why some are better than others.

You’re not going to take great photos just by knowing how to operate the camera mechanically. You need to know where to be and when to press the button.

And in the same way you won’t write good programs just by learning a language. You’ve got to learn how to communicate with the language.

So, to write clear code, you’ve got to read a lot of code.

Good stuff, yes, but you also need to read a lot of shit to learn what not to do.

And you’ve got to write a lot of code too.

Open source code is great for this. Go to GitHub, open up a library and read it. Try to understand how it works.

Then try to re-write it in a way that makes more sense to you. Or maybe port it to a different programming language.

The point is that you need to practice.

But not just code.

Learn how to convey ideas through writing.

Read a lot.

And remember, it’s not only the science parts that matter.

As programmers, we get to do a bit of everything.

And that’s what makes it fun.

Thanks for listening!