Building Beauty: Week 3

Studio

This week was mostly focused on getting feedback on our ornament projects, with the presentation at the end of the week.

I was originally thinking to make something out of the clay we used in week 1, but was inspired by the direction of a couple of other students in the class.

I had the idea to make a box for my AeroPress filters.

Currently I just use a little tupperware container, which is pretty gross. It’s been annoying me for a long time, but I just haven’t come across anything nice to use instead.

While I wanted a small enough project to be achievable within the timescale, I was a bit concerned that a box might be a bit difficult to make interesting enough. I’m not great with decoration, so I did a bit of research for inspiration.

I came across Kumiko, which is the Japanese word for the lattice work within the frame. I’ve not done much fine woodworking, so I thought this would be a good way to add more ornament into the box without it becoming too busy (or difficult!)

If I’d have been making this before the course, I’d have probably used SketchUp (a 3D modelling tool) to draw out this to the millimetre.

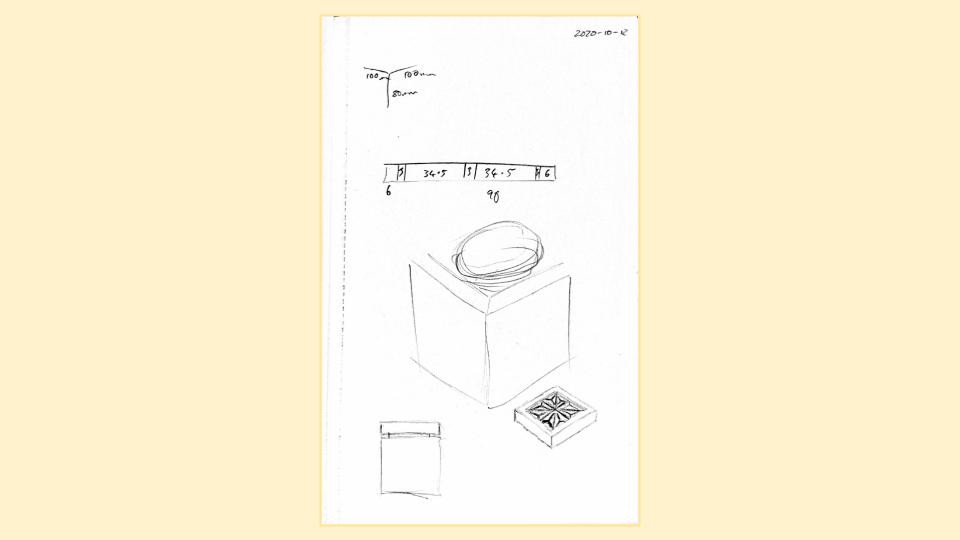

Instead, I decided to approach this as an experiment on the extreme end of building by feel. I sketched out a really rough idea just to get a feel for the general concept.

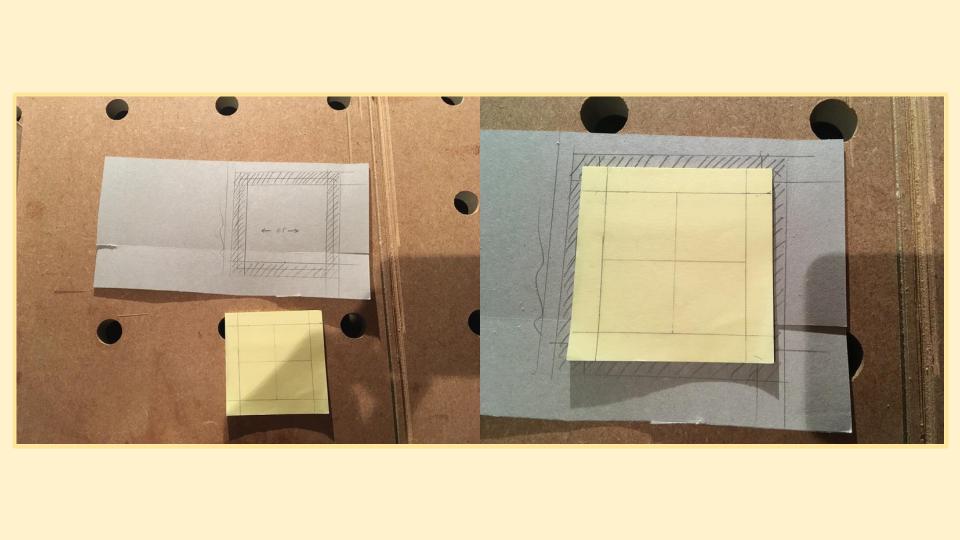

I mocked up the box with some card so that I could put it in context.

This was really effective in understanding proportions. It made it really clear that it should be a little smaller so that the row of boxes forms a gradient.

I also noticed that there’s an echo in the form of the circular elements of the existing boxes. Each is slightly different, but it was clear that the new box should incorporate an echo of this.

Prototyping is also useful from a functional point of view.

I wanted to check that I could get my fingers to the bottom of the box when I’m running low on filters.

After I’d bought some materials, I used the prototype to set the boundaries of the form, and then used the materials themselves to set the rest of the dimensions.

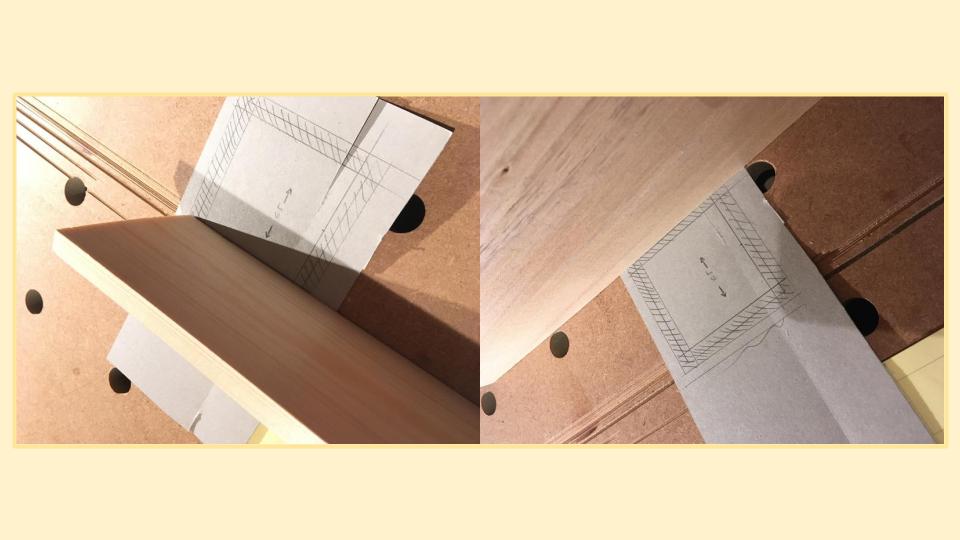

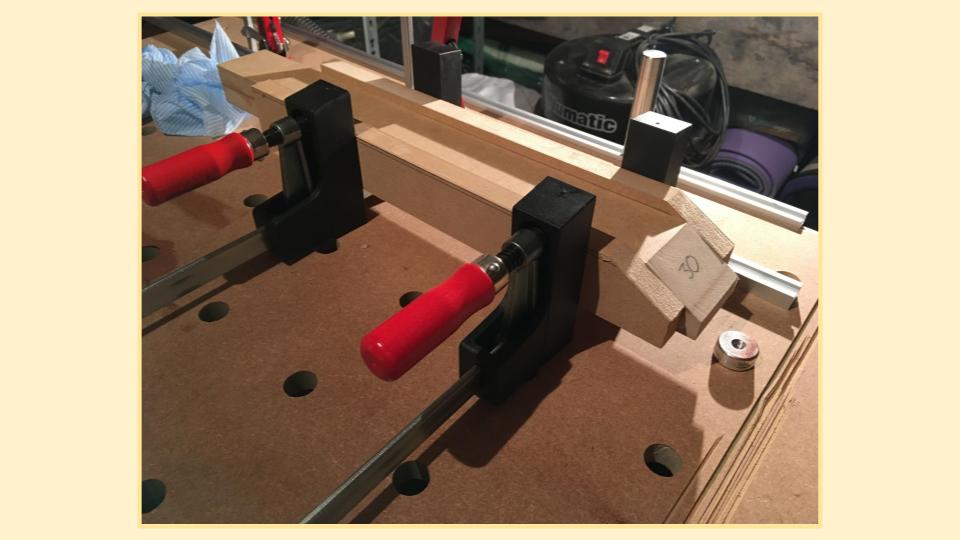

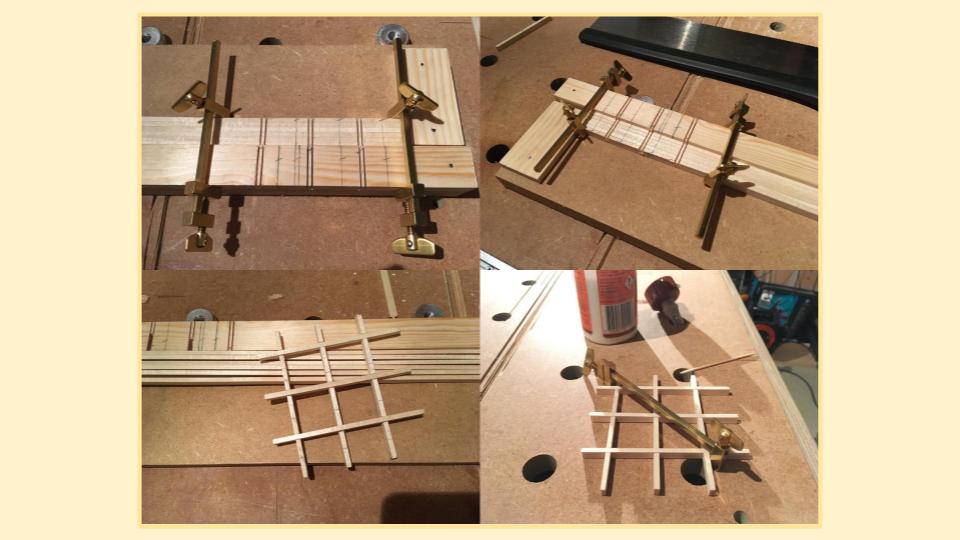

I had to make some jigs to make the Kumiko. These had to be quite precise so that the angles would meet nicely. While roughness is a fundamental property, it doesn’t necessarily mean sloppy work!

Making the Kumiko frame…

I didn’t take many in-progress photos of making the box because I was short on time over the weekend I had to make it. This was my first time using primarily hand tools, so I spent a lot of time figuring out how to get them set up and practicing working with them, as well as actually making the ornament itself.

I found it pretty stressful to figure out the design as I went.

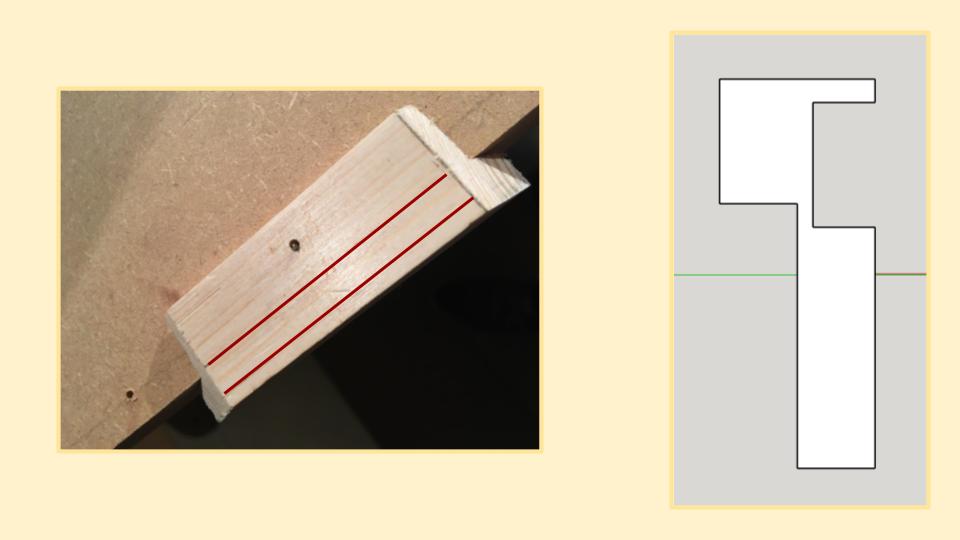

The way the lid turned out, because of the dimensions, it was actually really brittle because of where the groove had to go to place the Kumiko. I actually snapped one of the lid pieces by mistake. 🤬

It’s partially to do with experience, as with more experience you’ll have more patterns for designs that work, but it’s a good example of what to look out for in larger scale projects that need structural integrity.

I’d have possibly spotted this had I done more sketching during the construction.

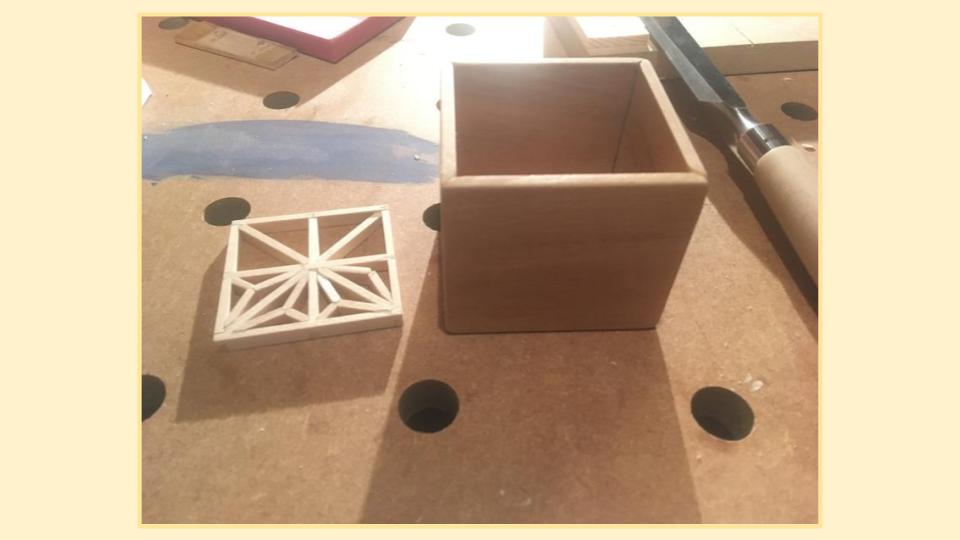

Box complete! Working on the Kumiko insert…

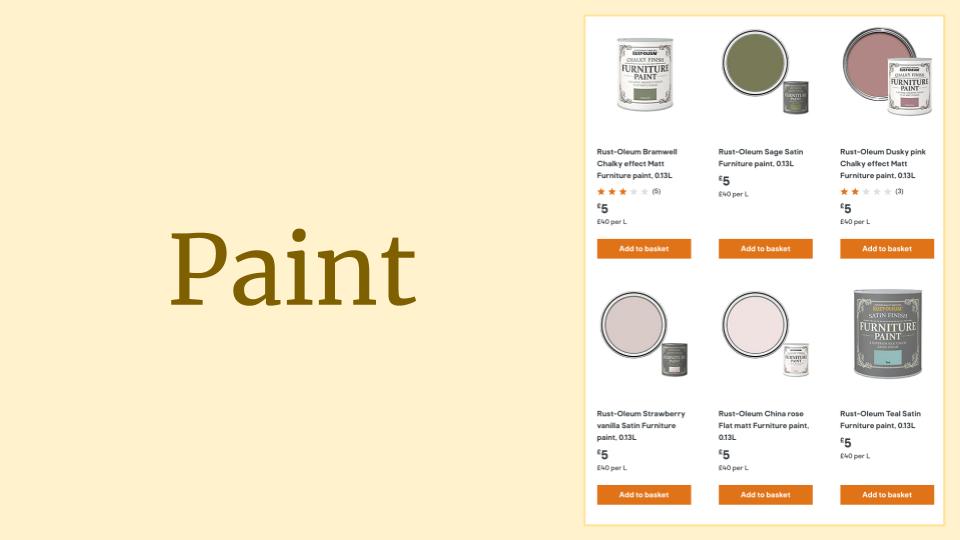

To add some contrast from all the natural wood, I wanted to add some colour.

It was clear that the Kumiko pattern needed some contrast, so the lid was the best place to do this.

It was also the least interesting wood, so felt like a good way to make an improvement to the overall composition.

I was originally thinking about a green or maybe a dusky colour.

I didn’t have lots of samples to hand, and it would be too expensive to buy several samples, so I added colour using the computer, but still using the mockup in context.

I was surprised to find that the blue worked best. I didn’t even think of it at first, but we actually have a handful of blue elements in the kitchen, so when I saw it in place it immediately clicked in my mind that it works as alternating repetition.

And here’s the finished result!

Overall I’m pretty happy with how the project went. It’s probably the most “ornamentation” I’ve added to a woodworking project, and also the first thing I’ve made using predominantly hand tools.

We’re working on our large scale individual project proposals for presentation next week. I’ve got a few ideas, but it’s tricky to make a decision given all the uncertainty at the moment. We’ll also be kicking off the next project – furniture!

Nature of Order

This week we focused on the latter half of the 15 fundamental properties.

- Deep Interlock and Ambiguity: Looping, connected elements promote unity and grace.

- Contrast: Unity is achieved with visible opposites.

- Gradients: The proportional use of space and pattern creates harmony.

- Roughness: Texture and imperfections convey uniqueness and life.

- Echoes: Similarities should repeat throughout a design.

- The Void: Empty spaces offer calm and contrast.

- Simplicity and Inner Calm: Use only essentials; avoid extraneous elements.

- Not-Separateness: Designs should be connected and complementary, not egocentric and isolated.

Again we did an exercise to understand these properties; this time we picked an image that we considered to have the properties, and one we thought didn’t have them.

The Traditional Garden

- Very few straight lines

- There are infinite levels of scale

- Boundaries are blurred through the use of foliage

- Trellis binds with the wall

- The wall and tiles form a gradient of similar colours

- The tiles create roughness through their texture and subtly graded colours, and through different sizes

- Greenery growing up the post – connects the frame with the ground and the grass beyond

- The “tunnel” formed is like a void of infinite depth

- Individual elements themselves have life – the iron benches, the collection of plant pots, the individual roses

- The sunlight on the tiles creates a centre in itself

The Modern Garden

- Everything is straight and precise

- There’s no gradient at any of the boundaries

- Nothing has good shape

- There are few levels of scale

- Each area is completely separate with a really hard border

- The few natural elements – the trees in the planter – even seem to have had all the life sucked out of them

- There are no strong centres

- None of the centres support each other; they all want to be their own individual element

Chose this property for these pictures because, well Chris said it’s the most important property, but also I think this is the key result of the design decisions made in each. In the modern garden all the centres are totally separate.

Chris spends a lot of time of vary careful observation with structured recordings. He takes lots and lots of examples and each is very carefully chosen. They are precise and expressive.

Paying close attention to the words you use helps to really pinpoint meanings with accuracy. Because of this, and the pictures, you experience each property.

When getting into arguments about whether you like something or not, always get back to the centres – the technical arguments.

We should take care to witness what’s going on in the world to avoid becoming disoriented and lose meaning.

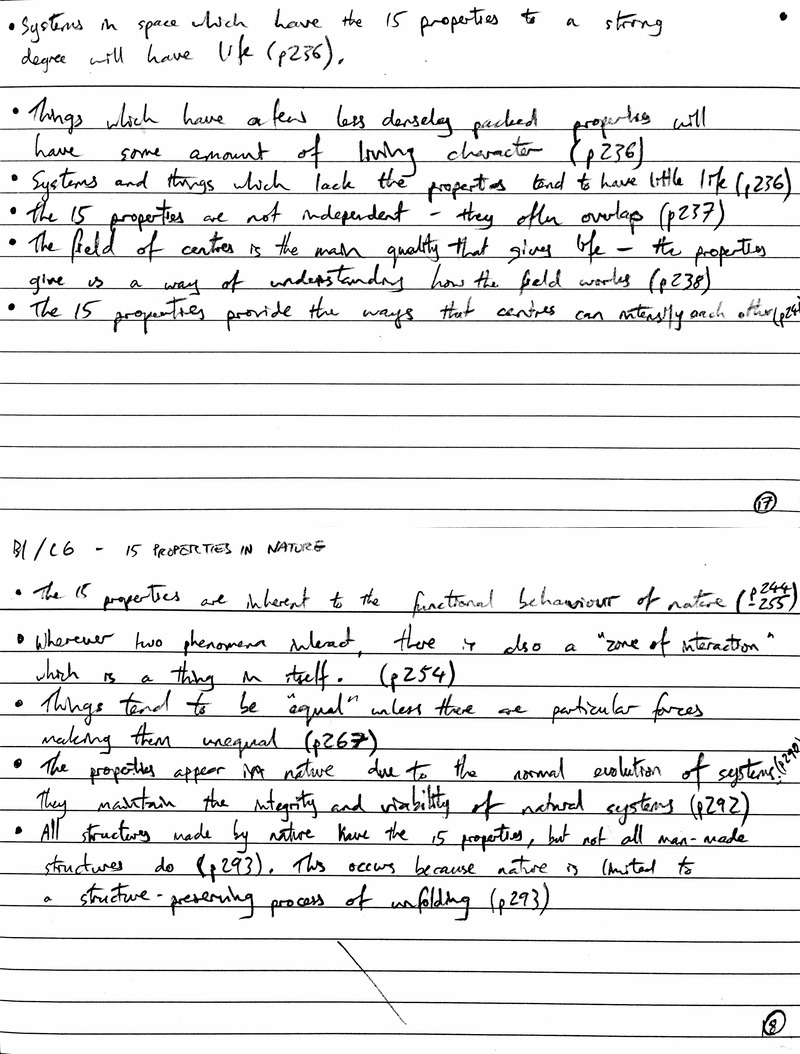

I was a little ahead of myself on reading this week. Along with the remaining 15 properties we were covering the 15 properties in nature. While interesting, there wasn’t much new information, so took fewer notes on that.

Beautiful Software

This week we started the Beautiful Software seminar. Greg gave an intro on the course, and a bit of background on Alexander’s work in the computer industry so far.

The original material gives you a grounding on what Alexander considers “good” in the world, and you can apply this to other domains. It can be difficult to learn how to apply the ideas intuitively from the books alone though.

The patterns people – The Hillside Group – started with patterns as a useful way of communicating. At that point Alexander had moved on from patterns. He’d observed people making tiny local improvements from A Pattern Language, but the whole buildings didn’t have a better overall wholeness.

Lots of fashions of programming come and go. The result is that we just have to get used to the quirks of various frameworks and languages. They’re very close to a logical system. Some are improvements, but it’s like the local improvements gained through APL.

So what’s the point of the computer programme? You’d end up being an odd person in a group of normal software people. We have to meet some of the criteria that some of the computer industry deems successful.

In order to be successful in conveying Alexander’s sensibility we have to make things that are successful ourselves. Having influence is not just about money in the computer industry. Steve Jobs wasn’t considered super wealthy for a long time.

The “Design Patterns” were a way to avoid some of the problems that manifest in software, but they’re mostly a very technical thing that did not give you a better sense of judgement as to whether something is good or not.

How do you figure out and separate out the stuff that’s working well vs the stuff that isn’t? The small details aren’t that important – you don’t want the parts to overcome the whole – and patterns focused on the details.

Will Right – who did Sim City and The Sims – read Nature of Order. We convinced his design team to read Nature of Order. I don’t know what they got out of it, but they didn’t come back, so we learned that just handing off the books didn’t really create much momentum.

We spoke about what we feel like success looks like. A repeated theme was being able to define and demonstrate beautiful software.

Alexander did Eishin so that people could experience a modern building that demonstrates the qualities he speaks of.

A carpet is a really tangible thing that has an impact on you, but we have different criteria in our domain. Our version of “clarity” is different. What does a beautiful codebase look like? What is the criteria that we use to judge it? What does beauty look like at the different levels of scale - down in the weeds of the code, to the user interface and interaction design, and up to the processes you use to organise work?

There’s a Russian version of A Pattern Language which in itself is beautiful, but they also demonstrated their process for making it. There are lots of interesting sequences in software development. How do we document and inject life into them?

We’re continuously comparing code to output (e.g. switching between terminal and web browser) – it feels like there should be something between the two. The way that the output is generated is kind of hidden and you have to hold it in your head.

Would we discover things about the code if we started from an unfolding perspective? Can you facilitate the “next right thing” workflow within a development environment? The initial pitch for Gatemaker was about centres; it was a project to help us understand that more.

We’re also inspired by the thought of feeling alive while you build something. It seems like you get that feeling more with physical stuff. How do you achieve that while writing software?

The problem with Visual Basic is that it can’t get you all the way there. You have to create something that works at every level – start, finish, repair. Some sequences are just repair sequences.

I should just be able to say “draw a square” on the screen. Back in the 90’s UML was all about making things rigorous and typed checked. Starting with classes kind of ignored the problem. Don’t you want to design the system starting from what you’re trying to achieve? Seems more practical for consultants.

Chris gave a lecture at the OOPSLA conference in 1996. At some time during the lecture he said you have the power to make real change in the world and if you’re a hired gun you won’t get to do this. There’s an idealism in the computer industry that wants change to happen in a way that empowers people. Computer people need to realise they can make it so.

We’re not that interested in making big corporations bigger. We want to produce things that are genuinely good in the world. While good things come out of consultancy, it’s harder to do that as a consultant, since you’re generally helping achieve someone else’s vision.