Building to Learn

Dealing with uncertainty is inevitable when working with creative problems.

It’s natural for humans to crave certainty. We like to know what to do. We like to know when we’ll be done. We try to build roadmaps to feel like we have the answers.

A lot of the time we don’t know what to do, when we’ll be done, or what the answers are. We’re working with problems that have never been solved before, and our job is to figure it out. This is about how we go about building something when we don’t know where we’re going.

Complicated Problems

Before we get to that though, we should look at situations where roadmaps do work. Though there are lots of general problems with roadmaps, they’re fine when you understand both the problem and the general solutions that can be applied to solve the problem.

A concrete example of this building a blog:

- We find a blog engine that we like.

- We develop a theme and apply it.

- We configure the domain and hosting.

- We start publishing.

This is what’s known as a complicated problem. There are a few steps between goal and success that take specialist skills to solve, but even with some variance between projects, the chain of cause and effect is understood enough to have a high confidence in success each time.

Complex Problems

We’re often faced with a much fuzzier situation, where we have to both define and solve a problem1.

We’re usually looking to achieve an outcome – “which book should I read next?” for example, but there’s no right answer and it doesn’t come with instructions on how to achieve it.

There are 130 million books in the world, so before we can even start thinking how to answer we need to set some constraints to make the problem manageable. If our product is used for finding fiction books, we might constrain the answers to a few different genres based on the last 3 books the user has read. Or if someone is trying to learn a new language, we’d constrain our problem to that language and an appropriate reading age for their skill. How to increase your odds is a whole other topic, but this act of setting the context and defining boundaries is defining the problem.

Once you’ve arrived at the problem definition you still need to solve it. There are several different approaches we could take to arrive at an answer – always more than we can attempt with the resources we have – and it’s never clear which option will yield the best results. We make an educated guess at which we think will work best and try it so that we can sense whether we were close to providing a good answer or not.

This can all be summed up as a complex problem. There are no definitive answers and you only understand whether you were successful after the fact. A roadmap totally doesn’t work in this context because it relies on you knowing what to do up front. A complex problem requires a series of probing steps and analysis of feedback to fumble your way towards the goal.

You build to learn.

I’ve found that there are two main tools that help manage a project where you’re building to learn – bets and journals.

Bets

When we know how to be successful, we can focus on making our solution better for the user and cheaper for us to produce.

When the project is to figure out what success even means, we’re much more interested in finding a solution that yields great results while avoiding going the wrong direction and only finding out after we’ve spent 90% of the resources available to us.

While we try our best to make good choices to chart our way through the metaphorical minefield of possibilities, we only get to find out whether we succeeded after the fact.

In this type of context we don’t plan with roadmaps and tasks. “Planning” implies certainty. “Betting” uses the language of risk.

A good bet means making an informed choice over what you put in and capping your downside so that you know there’s a limit to what you’ll lose.

In the early stages of a project we use lots of techniques to set the context of a problem. We’ll talk to users, gather data, and use low-fi sketches and breadboards to rapidly try out different ideas to hone in on what feels like the best direction. We’re trying to understand the situation users are in and the progress they’re trying to make.

As we get a deeper and deeper understanding of what we think might help them make progress, we can decide on an approach and shape that into a high-level description of what we’re going to build. This is a bit of an art in itself, but the main thing we’re trying to do is articulate the solution in a way that’s concrete enough that we can imagine the finished artefact, but abstract enough that we have room to manoeuvre when we get into the building.

Understanding the problem and shaping what to build help us make an informed choice of where to bet our resources.

On the other hand we want to minimise risk. We do this by setting fairly hard time constraints around chunks of work, but allowing variable scope so that we have flexibility in how they’re implemented.

The time constraint focuses the mind on what’s absolutely core. We want to make sure we build out all the unknowns before we worry about which shade of blue to use, or how many error cases to handle. We’re constantly changing our mind about what we build within the boundaries of the shaped work, but we know we’ll end up with some version at the end of the time-box.

You can’t look at a solution in isolation to assess whether it works well; it must be put to real use. Shipping some version of our solutions to real users is critical to get feedback so that we can analyse whether we were close to a good answer to our problem.

Most projects are a collection of several bets, so minimising the risk of any one of them being a disaster and losing all our resources helps us make a series of good bets, of which hopefully some pay off!

This malleability of the work means we can’t define all the tasks up front. A large portion of the work is actually figuring out what work to do – much more so than in a complicated project where you have a rough template of tasks and spend most of your time building. So instead of a planning tool that looks into the distance, we use a tool that leaves breadcrumbs so that we don’t get lost.

Journals

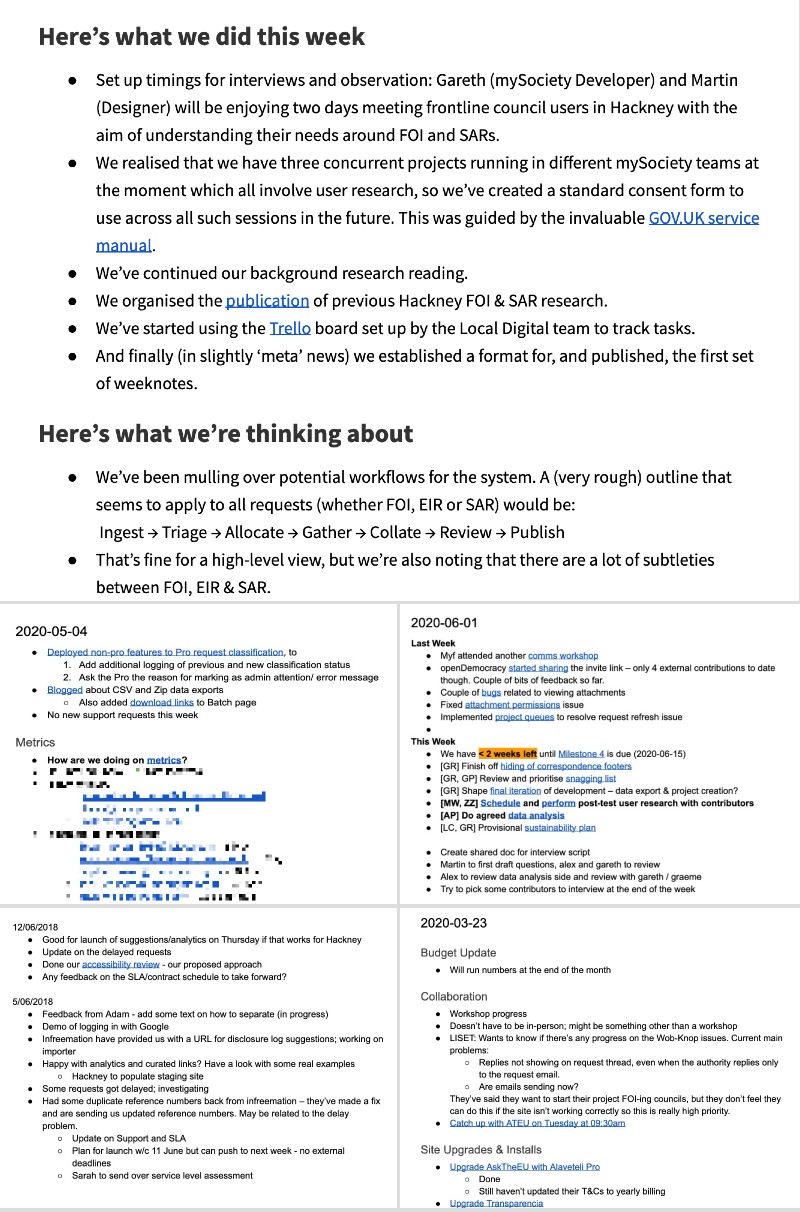

Much of project management can be summed up as wanting to know “What got done?” and “What are we doing next?” This is the job of the journal.

When dealing with complex problems I prefer a much looser system than heavily structured, process-oriented tools. Each problem is always different, so I find I’m frequently hacking and moulding the process as I get to grips with the project. The best tool I’ve found for this is Google Docs; the word-processing and collaborative editing features are best-in-class.

I’ve used a few varying journal formats tailored to specific projects, but the gist is similar to the weeknotes movement. Each planning cycle starts with a dated header and should have sections that cover “What got done?” and “What are we doing next?” 2.

With complex projects you often can’t see very far ahead. You have to interact with the problem to get some feedback and sense where to go next. While some tasks can be defined up front, many of the things that you need to do emerge over time as you climb the hill, reducing the need for complicated task allocation systems. Instead, we constantly review the journal and use it as a prompt to ask the right questions that shine a light on where to step next.

The key to journals is that they’re terse and information dense. Entries should clearly articulate progress in as few words as possible. “Started building X and the big technical unknown was much easier than expected”; “Blocked on Y because design allocation used this sprint”; “Merged Z so only a few minor bits remaining”. They act as a timeline that someone at arms-length to the project should be able to quickly scan to understand interesting key findings and direction of travel without having to dig deep into the details.

A good journal reduces communication-proxying. Entries should link out to places where the work is actually getting done – GitHub issues, mailing list posts, other Google Docs, etc. Outsiders can follow the links to find out who knows most about an entry and asynchronously ask questions in the context of the work.

Journals leave a trail of evidence from problem to solution to analysis. We can lay markers at points where we got lost, changed direction and struck gold. This helps us learn the causality between goal and success, so that we can hopefully convert the complex problem into a complicated problem the next time around.

Summary

A complicated problem has a range of right answers that requires specialists to analyse the cause and effect of different options. You broadly understand how to tackle the problem so you can use planning tools that lay out the steps up front. You can improve the outcomes by increasing quality and reducing costs.

Complex problems have no definitive right answers and you can only understand cause and effect in retrospect. Planning tools must cater for exploring many unknowns and sensing feedback to learn about the problem and learn what solutions may work. Getting good outcomes relies on finding best-fit solutions and avoiding disaster.

Further Reading

- Complexity: Removing software as the inhibitor of Agile, How leaders change culture through small actions

- Shaping & Betting: Shape Up, Thinking in Bets

- Journaling: Bulletins vs bulletin boards

Footnotes

1: I think about this in terms of the mathematical definition of a problem – “an inquiry starting from given conditions to investigate or demonstrate a fact, result, or law” – rather than “an unwelcome matter or situation”.

2: They don’t need these exact titles, but the entries should answer those questions in a way that makes sense to the project.