Shaping Software with Context, Boundaries and Language

There’s always more than one way to enable an outcome, but we usually have limited resources, so we’ve got to make a call on an approach. To make sure our resources are spent effectively we shape the work and make a bet.

The majority of software development takes place within an existing system, and figuring out how to integrate new pieces of development is a challenge in itself. There are three key things I look for when shaping work for an existing system: Context, Boundaries and Language.

It’s easier to walk through these concepts with an example.

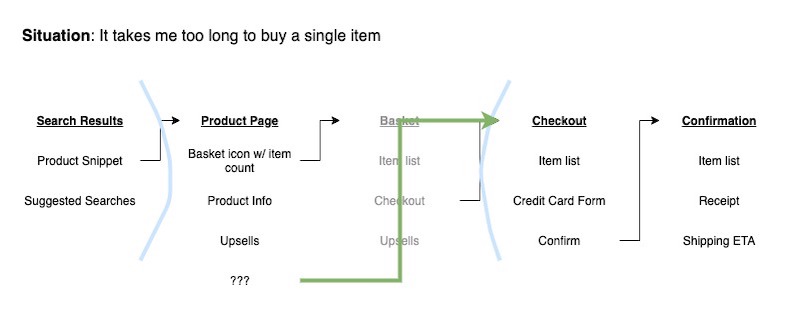

Let’s pretend we’re working on a fairly standard e-commerce site, and a struggle we’ve noticed through talking to customers is that they feel it takes too much effort to buy a single item.

We’ve reviewed some data and found that only 15% of customers buy just one product, so there’s not a huge appetite for this. We have noticed that there’s a higher abandonment rate for single-item baskets though, so we’d like to do something.

Context

The first thing to map out is what you’re integrating with.

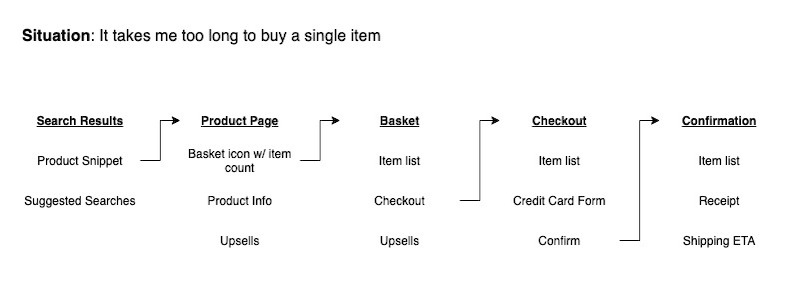

I usually start by jotting down the specific situation that we’re trying to resolve, and then breadboard the steps they currently take until they reach some sort of conclusion – a point at which they effectively end a journey.

This gives us a sense of which parts of the system we may need to change. Breadboards are a great technique for this as they’re very informal and intuitive.

Boundaries

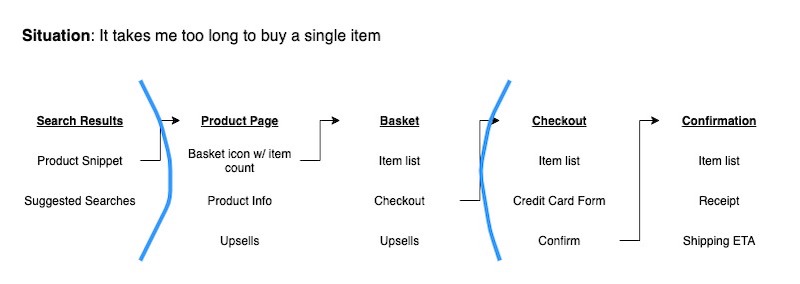

Now we’ve laid out our context we can start to play around with ideas for how to resolve our customers’ struggle. As we do this, I’m looking for boundaries – parts of the existing system that we don’t want to touch.

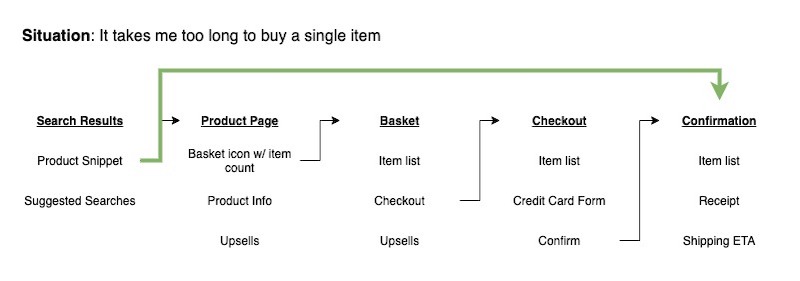

The first idea we might explore is to skip the most steps possible and take users straight from search results to a confirmed order.

We don’t currently store card details, so we quickly decide that it would be far too much work to build this idea within the appetite we have. We also decide that we want customers to view the product page because there are important details that we can’t easily show in the search results.

We now know we have to go through the checkout step, and we don’t want to change the search results page. We’ve set our boundaries.

Boundaries are important for limiting the scope of development to fit within the appetite. Without clear no-go zones, it’s too easy to end up changing vast amounts of the system and before you know it you’ve spent double the time you were expecting.

Language

With a good understanding of what we’re working with and boundaries in place, we’ve started to narrow the set of solutions that might work. The places we’ve allowed ourselves to change are limited to the product page and the basket, so our solution becomes clear – we want to skip the basket.

We could leave it here, but we’re still missing some important information – domain language.

If we’re doing the work ourselves, and certainly for this toy example, we could probably get away with figuring it out as we go. When we’re handing work to others to complete, and especially with more complicated examples, we need to be able to describe what to build.

For all but trivial changes, we can’t spell out all the details in advance, but we want to be confident that there’s a shared understanding of the solution.

Without developing good domain language this description might be quite vague and technical. It lacks coherence and includes unresolved issues that may lead to to mis-interpretation and blockers.

Reduce the time it takes to buy a single item by skipping the basket.

We want a button on the product page that skips the basket when someone wants to buy only that product. We need to somehow add the product to the checkout, which currently uses a basket as its source of items.

There are three problems with this description that warn us that we haven’t shaped the work well enough yet.

- We’re overly specific that a button will be used to trigger the new workflow, but give no language that describes the overall concept.

- We hint at a technical issue we’ll need to tackle so that we’re able to add items directly to the checkout, but give no indication of the direction we’ll take to overcome it.

- While the breadboard may be useful to refer back to, it includes too much incidental information from our workings out, and not enough information about the solution we actually want.

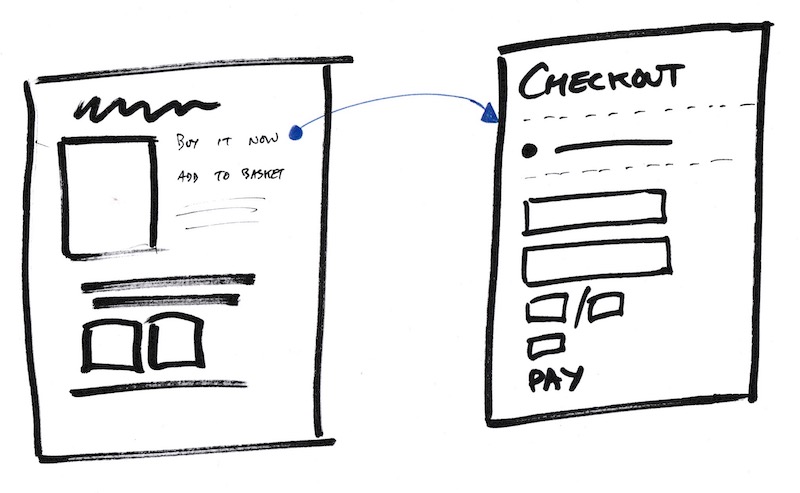

We can refine the description of the work by developing domain language to describe the new parts of the system, and include a fat marker sketch to help visualise the flow a customer should experience.

Reduce the time it takes to buy a single item by skipping the basket.

From the Product Page a customer chooses Buy it now which adds the Product to a Temporary Basket that’s immediately loaded by the Checkout.

Now we have a crisp and concise description of the work that makes implicit concepts explicit, and articulates the relationships between components and how they should interact.

We haven’t had to spell out every technical detail, and we leave plenty of room for the implementation details to be decided during the building.

Crucially, we’ve designed a solution within clear boundaries to minimise the risk of getting too deep and running out of time. We know how it will integrate with the existing parts of the system, and we’ve done the work in enough depth that’s allowed us to build good domain language for the core concepts we’ll use to build the solution. This gives us confidence that there are no major unknowns that will surprise us when we start building.

Further Reading

- Domain Driven Design: Chapter 2 – Communication and the Use of Language

- Shape Up: Principles of Shaping

- Find Context Boundaries with Domain Storytelling [video]

- Boundaries within the codebase [video]